2024 AI LEADERSHIP SUMMIT HIGHLIGHTS

16/06/2013

Paper presented to the International Summit of Business Think Tanks by CEDA, Chief Executive, Professor the Hon. Stephen Martin.

Introduction

It is a given that countries need to innovate to maintain and improve living standards in an increasingly competitive global economy. Improving productivity and competitiveness through innovation and skills development, to help create new business opportunities, growth and skilled jobs for the future, are essential in achieving these objectives.

Productivity principally drives national prosperity in the long run. Innovation is a tool to facilitate growth in productivity, market diversity, exports and employment. Significant benefits accrue to business and, in aggregate, the economy and society, where a culture of innovation is pursued. Innovation also delivers greater resilience at a business and an economy-wide level, greater ability to handle shocks and changing business and economic conditions.

Innovation is often perceived as world-first breakthrough technology underpinned by research and development but it is much broader and more pervasive than this. How business responds to the innovation challenge therefore is a major determinant of its capacity to lift productivity and to add to a nation's wealth.

The question that remains critical to improving competitiveness and productivity through innovation is whether there is a role for government in developing public policy to support fundamental change and improved economic and social well-being, and if so what is the best way for government to provide this?

This paper seeks to describe and provide some analysis of the public policy approach to innovation adopted in Australia by governments at the national and state levels. It examines the current approach of the Australian Government in developing an annual innovation system report, the financial support that is provided and the way in which business responds and contributes to the development of public policy at this level.

Additionally, the strategic approach to innovation adopted by various state governments is examined, and analysis provided of the interconnectedness between national and state governments, public policy development across jurisdictions and the way the business sector pursues an innovation culture that when combined add to the nation's productivity and competitiveness.

Government approaches from Australia are proffered as policy solutions applicable in other economies.

Background

Australia's economic strength, fuelled by the resources boom and the rise of Asia, is driving structural change in the Australian economy. The terms of trade, the appreciation of the Australian dollar, and high capital investment in the resources sector have all driven a growth in incomes, but have also created pressure on parts of the economy, especially manufacturing. Coinciding with this has been an apparent slowdown in measured productivity across most advanced economies.

With evidence that the resources boom may have peaked - with terms of trade easing and mining investment peaking - Australia needs to boost productivity to ensure that real income growth is maintained. Innovation is the fundamental link to productivity and competitiveness. Evidence of the link between innovation, productivity and global competitiveness is strong.

The Asian Century offers tremendous opportunities for innovative Australian businesses. Impressive growth and the rise of more middle-class consumers in Asia will mean greater demand for what Australia has to offer - not only in the resources sector but also in areas like energy, water, agriculture, business and financial services, education, tourism, health and high technology manufacturing.

Australia's comparative advantage will only be sustained in the face of international competition through companies enthusiastically embracing research and development (R&D) and recognising the benefits that innovation can bring. Governments have a role, but they are not the only players. That said, it is important to understand what the role of government should and can be to sustain a robust economy through innovation.

Innovation agenda

The Australian government, cognisant of the structural changes facing the Australian economy over the next decade, undertook policy work and research throughout 2008 to develop a 10-year innovation agenda Powering Ideas - An Innovation Agenda for the 21st Century, released in May 2009. In doing so, it drew on numerous reviews that examined specific industries such as textile, clothing and footwear, automobiles, pharmaceuticals and higher education. Additionally it specifically examined innovation policy options including reviewing the existing innovation framework which provided the basis for a reform agenda.

The report identified a poor business innovation record and lack of collaboration between research and industry as the two major weaknesses of the innovation system. To address these weaknesses, the report identified seven National Innovation Priorities (NIPs) which help to inform innovation activities and incentives provided by the government1. These were:

- Priority 1 - World-class research: increasing the amount of research generated at a world-class level, benchmarked against international performance levels based on the world average citation rate by field of research.

- Priority 2 - Skilled researchers: increasing the number of skilled researchers by increasing the number of students completing higher research degrees.

- Priority 3 - R&D investment: increasing productivity by promoting the number of businesses investing in R&D with the aim of developing new-to-the-world innovations.

- Priority 4 - Business innovation: increasing the share of Australian businesses carrying out innovation by 25 per cent over the decade to 2020.

- Priority 5 - Collaboration between industry and researchers: to address Australia's poor track record when it comes to collaboration and commercialisation of ideas.

- Priority 6 - International collaboration

- Priority 7 - Public sector innovation

Federal Government programs

To assist innovation, governments at all levels provide a variety of programs and incentives to support the NIPs, their priorities reflecting national or more local imperatives.

Federal Government programs focus on providing incentives for businesses to innovate (improving access to finance and R&D funds), developing a skilled workforce and improving Australia's capacity to innovate through skills acquisition, research and collaboration.

Australia's research capacity spans a number of sectors, including biotechnology, nuclear science, space and resources. Government policies are focused on funding research infrastructure but also directly funding relevant research activities.

In 2010-11, the Federal Government spent $8.47 billion on science, research and innovation, 20.4 per cent of which were on its own research activities, 22.4 per cent on business innovation, 30.7 per cent on the higher education sector and the remaining 26.5 per cent on various sectors including health, energy and regional R&D as shown below2.

Of critical importance is the National Research Investment Plan, released in November 2012. Created by the Australian Research Committee, whose role is to provide strategic and integrated advice on research investment, the plan sets out a national research investment planning process3.

Government funds for R&D and financial assistance to carry out research and innovation are currently allocated on several bases. Individual research project fund seekers are chosen on a competitive basis, higher education and rural researchers obtain funds on a formula driven basis while government research agencies and specific subject area research are given direct allocations.

The Federal Government has allocated $8.9 billion towards science, research and innovation for 2012-13, including $4.0 billion (45 per cent) towards publicly funded research, $2.1 billion (23 per cent) towards business research and $1.3 billion (15 per cent) towards research workforce development as shown below.

Source: 2012 National Research Investment Plan. Figures and shares based on budget allocations. Actual final figures and share may vary.

Australia's national innovation system

Tracking the performance of Australia's innovation system is essential in assessing its contribution to the nation's economic well-being. The Federal Government's Australian Innovation System Report (AISR) is used to monitor performance by analysing actual achieved targets against targets set in the innovation agenda.

The report discusses trends in innovation in Australia and where possible benchmarks Australia's performance against other OECD countries. Given the importance of Asia to the Australian economy, this is perhaps an issue that requires further consideration in future reporting to make meaningful, wider-ranging comparisons.

What the report seeks to offer is robust, practical and relevant measures of innovation with a focus on skills and research capacity, business innovation, links and collaboration, and public sector innovation.

Research performance

Research performance is based on the amount and quality of research being undertaken. From 2006 to 2010, Australia's performance remained unchanged, recording higher than world average citation rates in 19 out of 22 fields. It also fared well on other research indicators, including improving its share of the world's top one per cent highly cited publications in the natural sciences and engineering field as well as the social science and humanities field.

As measured by gross expenditure on research and development (GERD), Australia's research funding fell to 2.22 per cent of GDP in 2010-11, compared with 2.24 per cent in 2008-09. Australia ranks seventh in the OECD when it comes to government-financed GERD, at 0.77 per cent of GDP compared with an OECD average of 0.68 per cent.

A major feature of research in Australia is the orientation towards industry and innovation. There has been considerable discussion around the issue of the research sector (that is universities, the government and private not-for-profit organisations) reorienting itself towards research which can be more easily commercialised or translated into economic development and success, that is, applied and experimental research.

Applied and experimental research's share of total research has been rising since the 1990s. However, the research sector continues to lag behind the business sector. Applied and experimental research currently accounts for between 50 to 70 per cent of research expenditure, compared with about 94 per cent for private businesses.

The performance of research commercialisation has been mixed. A Federal Government initiative, Commercialisation Australia, has been established to provide financial assistance and networking support to businesses and researchers wishing to commercialise innovative intellectual property4.

Skills performance

Education, and in particular, a skilled labour force is crucial for Australia's productivity. Lack of skilled persons is a major barrier to innovation for businesses5.

Over the past five years, the number of students completing higher degrees by research has been on the rise, consistent with the second National Innovation Priority. AISR notes that the growth is primarily due to international rather than domestic students. It also notes that while Australia's R&D personnel and researchers as a proportion of the labour force is higher than the OECD average, its skills base still displays some weaknesses, particularly in the science, technology, engineering and mathematics (STEM) fields. Gender imbalances continue to persist in sciences, while secondary schools have noted lower participation rates in mathematics, physics and chemistry. Furthermore, the report highlights an impending shortage of skilled researchers and R&D personnel due to the ageing workforce.

The report notes that innovative businesses are more likely to indicate that they face skills shortages than businesses that do not innovate. In response the Federal Government has developed numerous programs to address the skills needs of the nation, including the Research Workforce Strategy (RWS).

However, a skilled workforce alone does not necessarily lead to innovation - business needs to have strategies in place to ensure that their employees' skills are being put to their optimal uses. The AISR identifies a variety of strategies that have proven successful to enable innovation, including: supportive leaders, an inclusive workplace and ensuring employees remain motivated. Training and flexible labour market conditions (e.g. flexible work hours) also support innovation through skills development and better allocation of labour resources.

Business innovation performance

Innovating businesses have indicated that while the pursuit of profit is the main driver of innovation other contributors include responding to consumer needs, market share strategy, improving quality and efficiency. About 96 per cent of business expenditure on R&D (BERD) is funded from non-government sources, primarily self-funding. In 2010-11, government funding accounted for about 1.8 per cent, or $3.24 billion6. The Federal Government provided the bulk of the funds at 83.3 per cent while the remaining 16.7 per cent was provided through state and local government programs.

R&D assistance to businesses through the R&D Tax Incentive is a major component of the business innovation program7. The incentive aims to promote R&D activities which would not otherwise have been undertaken due to market failures. It provides a 45 per cent refundable R&D tax offset for companies with revenue of less than $20 million per annum, and a non-refundable tax offset of 40 per cent for all other companies.

The aim of the R&D assistance and other business innovation programs is to meet National Innovation Priorities 3 and 4, namely, to increase the number of businesses investing in R&D and to achieve a 25 per cent rise in the proportion of businesses engaging in innovation over the next decade.

According to AISR 2012, the proportion of innovation-active businesses dropped to 39.1 per cent in 2010-11 from a peak of 44.9 per cent in 2007-088. However, the number of businesses registered for R&D tax concessions has been rising over the past five years. BERD as a percentage of GDP stood at 1.3 per cent in 2009, compared with an OECD average of 1.6 per cent, giving Australia a ranking of 12. The government's share of BERD is under two per cent, compared with an OECD average of 8.9 per cent, giving Australia a ranking of 27.

Overall, AISR concluded that Australia's business innovation performance has been relatively flat over the past few years. However, the report pointed out that innovation and the gains from investment may be under-reported due to the way innovation is reported by the Australian Bureau of Statistics.

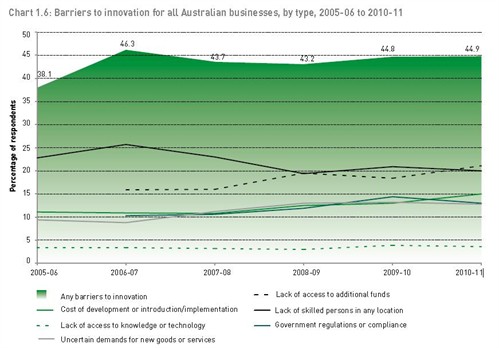

Despite government programs to facilitate businesses to innovate, businesses continue to report significant barriers to innovation. Of significance is the lack of access to additional funds and government regulations or compliance. In particular, red tape and a complex framework for R&D claims for Small and Medium Enterprises (SMEs)is a barrier to companies wishing to take advantage of the R&D Tax Incentive. Additionally, venture capital investment has been declining and this has affected the ability of businesses to finance innovation9.

Collaboration performance

As again noted in the AISR, the formal research sector and industry do not exist in isolation to each other. Collaboration between businesses and researchers is required to improve the quality of research being produced in order to support productivity and generate profit. Increasingly, as global competition continues to rise and the marketplace continues to become more globalised, collaboration needs to occur on an international level as well. Collaboration is crucial for innovation efficiency as it allows all parties to share knowledge, build skills, spread risk and achieve economies of scale.

The Federal Government has numerous incentives in place to promote collaboration in innovation. For example, the Transformation Research Program, administered through the Australian Research Council (with an investment of $236 million over five years to promote collaborative research between universities and businesses) will focus on fields such as engineering, nanotechnology and biotechnology. The program will promote doctoral students and researchers to undertake practical work in their field.

Despite existing programs and the benefits of collaboration, Australia performs poorly on this priority. In terms of the percentage of businesses that collaborate on innovation, Australia ranks 23 out of 26 OECD countries. The AISR notes that while the proportion has been on the rise, the proportion of innovative businesses that collaborate with the research sector has been falling in recent years.

The trend towards lower collaboration is reflected in patent filings. The proportion of joint (industry and research) patent filings has been falling over the past decade. The biotechnology and pharmaceuticals sector accounted for a significant amount of new patent filings over the past decade, most of which were not joint filings. However, collaboration between research institutions has been on the rise.

Australia's international collaboration performance has been weak with the share of higher education expenditure on R&D financed from abroad falling. However, the number of formal agreements on research collaboration between domestic and international universities has been on the rise. Global innovation has historically allowed Australia to become more productive as it has the local capacity to absorb imported innovations. Global collaboration enables Australia to acquire new technology, knowledge and highly skilled foreign labour, which have a flow-on positive impact on productivity.

A plan for Australian jobs

In February 2013, the Federal Government launched its latest innovation strategy, A Plan for Australian Jobs: The Australian Government's Industry and Innovation Statement. Essentially a politically-driven document to tackle business and union concerns in respect of manufacturing and future employment opportunities in the Australian economy, the government committed a $1.06 billion investment into productivity, prosperity and jobs over four years10. The plan will be funded by the removal of R&D tax concessions for businesses with an annual turnover of $20 billion or more.

Three strategies form the core of the plan:

- $125.9 million towards backing Australian firms to win more work locally through legislating that projects worth over $500 million have plans for local procurement, projects over $2 billion employ Australian Industry Opportunity Officers in global offices to qualify for tariff concessions and through stronger anti-dumping action.

- $514.4 million to support Australian industry to win new business abroad by creating Industry Innovation Precincts to promote collaboration and innovation in areas where Australia has a comparative advantage, as well as through facilitating commercialisation of innovation. It also includes $10 million towards expediting clinical trial reforms.

- $406.3 million to help Australian SMEs to grow and create new jobs, particularly innovative ones, by helping them win tenders and improving access to finance11. The government will set up Venture Australia, a package aimed at facilitating venture capital investment12.

Additionally the government will invest $11.2 million in the Manufacturing and Services Leaders Groups, which aim to promote collaboration between industry and government when it comes to innovation challenges.

The plan's release generated both support and opposition, with particular concerns being raised about the removal of R&D concessions for large companies. It was claimed that denying access to the R&D tax incentive for such businesses may run counter to some of the objectives behind the industry and innovation statement, would undermine confidence and add to international concerns about the stability and predictability of our tax arrangements. There was also claims that only $250 million of the announced $1.06 billion of funding was in fact new money.

It was also argued that these changes are contrary to the government's Asian Century White Paper's chapter on innovation. However, the plan signals a clear shift in emphasis to SMEs and was loudly endorsed by the union movement notwithstanding the Australian Council of Trade Union (ACTU) belief that contractors may be left out of the local procurement strategies.

Some pessimism was expressed about the Industry Innovation Precincts - how they will be designed and implemented in the absence of a specific implementation plan. It was suggested that the plan was borne out of the Prime Minister's manufacturing taskforce and as such had a very narrow focus13.

State programs

Each Australian state and territory has a different research focus based on regional opportunities and issues.

The most recent breakdown of GERD indicates that state and territory governments spent $1.31 billion in 2008-09, or about 4.7 per cent of total GERD. The funds were distributed as follows:

| R&D | Gross Expenditure R&D ($ '000) |

Share |

| Business | 27,696 | 2.1% |

| Commonwealth | 67,439 | 5.2% |

| State/territory | 728,346 | 55.6% |

| Higher education | 400,636 | 30.6% |

| Private non-profit | 85,063 | 6.5% |

| Total | 1,309,180 |

Source: ABS 8112.0, 2008-09

In New South Wales (NSW) the innovation emphasis is on information and communication technologies and nuclear science with the NSW Innovation and Productivity Council providing advice on facilitating innovation14. Five innovation policy goals have been set:

- Improving human capital;

- Upgrading knowledge and information infrastructure;

- Reducing the cost to business of using science and technology;

- Encouraging capital allocation to invest in innovation; and

- Reducing regulatory barriers to innovative companies.

In Victoria, the most prominent sectors are health and medical research as well as biotechnology. The Victorian Government believes that having strong innovation capabilities will help the state to overcome challenges such as climate change, international competition and the ageing population. To this end, the State Government funds and supports a number of programs within the science and technology fields, including the innovation voucher program15.

In Queensland, tropical and marine research is most common. As part of an Innovation Policy and Strategy the Queensland Business Innovation Report helps to measure the performance of innovation in the state. In 2010-11, the Queensland Government funded $295 million of R&D in priority areas including enabling sciences and technologies; smart industries and tropical industry opportunities16.

South Australia's Strategic Plan was formulated after consultation with scientists, researchers, innovators and industry. The plan aims to promote economic prosperity by creating a vibrant and strong community, balancing growth and the environment, and by investing in health, education and innovative ideas. The consultation resulted in an innovation strategy that concentrates on the key priorities for science, research and industry innovation. Climate change and water are two key research areas17.

In particular, innovation is seen as crucial to help South Australia overcome environmental, economic and social challenges, and for the long-term prosperity of the state. The plan emphasises the importance of improving South Australia's performance when it comes to venture capital, industry collaboration and R&D commercialisation, as well as public, business and university research.

Similar to the Federal program, the South Australian Government has set specific and measurable targets to reflect the key priorities and to enable them to track any progress made. Business, government, researchers and the community are required to work together in order to achieve the targets.

Not surprisingly, mining and resources research is prominent in Western Australia. The Western Australia Government's programs and policies focus on the state's strengths, challenges and opportunities, and aim to strengthen skills, link industry and researchers, extend research networks, attract research investment, fully utilise research infrastructure and capture the benefits18.

Tasmania's Innovation Strategy is focused on developing its areas of competitive and comparative advantage through innovation investment. Innovation policy is formulated by focusing on sectors that have the most potential to support the long-term growth of Tasmania19.

The Australian Innovation Research Centre (AIRC) identified areas which fall within this criterion, including: high-value agriculture, aquaculture and food; renewable energy; the digital economy; and tourism. Innovation programs are seen as complementary to private sector activities, rather than as a substitute for those activities.

The research focus of the territories also reflect regional strengths and challenges, with the Northern Territory focusing on tropical and desert knowledge20, and the Australian Capital Territory's research activities coming from the CSIRO and the Australian National University (ANU).

Innovation challenges and opportunities

With this myriad of government strategies, plans and jurisdictional overlap in place to support innovation, it is useful to consider two significant opportunities that serve as useful examples of where innovation and practical outcomes intersect.

As with most advanced economies, an ageing population is a key factor influencing the government's policy and innovation agenda. There is enormous scope for healthcare innovation in the coming decades to help meet Australia's ageing population challenge.

CEDA contributed to this debate by publishing a policy perspective in April 2013 entitled Healthcare: rationing the future.

Advances in medicine over the past 100 years have transformed human life expectancy and the management of illness. Australia has played an outsized role in this transformation with individuals having been at the forefront of disease eradication and the advances in medical technology. However, international comparisons highlight how our national capacity to translate research breakthroughs into medical benefits has been poor. Australia needs to capitalise on its existing comparative advantage in innovative industries, and take action to ensure they continue, if it is to enjoy ongoing prosperity as the high terms of trade normalise.

The nation has also developed a healthcare system that provides equitable and efficient healthcare services relative to many other developed nations. However, this healthcare system operates under increasing fiscal constraints and is already engaging in de-facto rationing of services. Ongoing technological developments are profoundly changing how much and how often people access healthcare services. This is creating a valuable export opportunity for Australia but also challenging existing funding mechanisms.

Unless substantial reform occurs, rationing will become more pronounced. Appropriate policy settings will enable Australia to build on its strengths and enhance the health of the population while encouraging the ongoing development of strong and sustainable high value economic activities in healthcare.

Accordingly the policy perspective makes a number of recommendations that cover translating research ideas into commercial reality; ensuring critical mass is obtained in commercialisation projects; funding 'killer experiments'; and maintaining an innovative economy through supporting STEM fields of study with incentives.

A second example relates to information technology.

The National Broadband Network (NBN) is Australia's first national wholesale-only, open access communications network that is being built to bring high speed broadband and telephone services within the reach of all Australian premises. The NBN will utilise three technologies; fibre, fixed wireless and satellite, expected to make possible improved ways for us to connect with one another. Within the next decade, the plan is for every home, school and workplace in the country to have access to the NBN21.

The Federal Government is underwriting the roll out of NBN to the tune of some $40+ billion. Political and technological arguments have raged since it was commenced with respect to cost effectiveness and technological efficiency. It is claimed that the NBN has the potential to transform many aspects of our lives including home internet and telephone services in areas such as education, business, entertainment and access to online health services.

For example, the government's goal is that by 2020, at least 12 per cent of Australian employees will report having a teleworking arrangement with their employers. The NBN will enable use of NBN services to access videoconferencing, virtual offices and the ability to upload large files from home. This has implications for future workplaces and urban design.

Delivery of education will also be fundamentally changed. Virtual classrooms, now becoming commonplace in higher education, will be enhanced in rural and remote communities.

Opportunities for advancements in medical technology are significant. The expansion of access to care through interactive internet consultations, supporting telemedicine and addressing health shortages through internet based care are some of the ways that services are expected to be offered to address the medical gap between urban and regional Australians. In the future, regional patients could have access to online services that provide the ability to consult with their specialist and local doctor simultaneously via video conference. Greater comfort as well as possible time savings and reduced cost are achievable.

NBN has the potential to change the way business is done by helping companies overcome the barriers of distance. Access to high speed broadband is expected to give businesses the opportunity to increase productivity, save time and money and the ability to compete on a global scale. Opportunities for businesses to hold virtual meetings or liaise with suppliers across Australia online - potentially saving time and costs associated with travelling - are envisaged through the use of this technology.

Conclusion

This paper has provided an overview as to the strategic approaches governments in Australia have adopted to the issue of innovation, the incentives they have sought to apply and the way in which business can have access to funding sources. What is clear is that there should be a role for government but that role should not increase compliance burdens on business: it should ensure that the taxpayer gets an appropriate return for any taxation concessions granted and that research programs return positive commercialisation returns.

There is no doubt Australia can do better in applied research, collaboration and commercialisation. There is equally no doubt that productivity improvements and enhancements can only come through improved innovation, whether it be by the application of scientific or technological breakthroughs or the application of managerial improvements that reflect flexible, modern and innovative approaches to work.

Professorthe Hon. Stephen Martin

Chief Executive

Committee for Economic Development of Australia (CEDA)

References

1. http://www.innovation.gov.au/Innovation/PublicSectorInnovation/Pages/default.aspx

2. http://www.innovation.gov.au/Innovation/Policy/Pages/AustralianInnovationSystemReport.aspx

3. http://www.innovation.gov.au/Research/Pages/NationalResearchInvestmentPlan.aspx

4. CommercialisationAustralia http://www.commercialisationaustralia.gov.au

5. ABS Cat 8158.0, 2012

6. ABS, Cat 8104.0, 2012

7. http://www.innovation.gov.au/Innovation/Policy/Pages/RDTaxIncentive.aspx

http://www.ausindustry.gov.au/programs/innovation-rd/RD-TaxIncentive/Pages/default.aspx

8. ABS Cat 8158.0, 2012

9. http://www.theaustralian.com.au/business/profit-loss/rd-tax-incentives-go-begging-because-of-excessive-red-tape/story-fn91vch7-1226557754990

10. See Australian Government - APlan for Australian Jobs: The Australian Government's Industry and Innovation Statement www.innovation.gov.au

11. Hon Greg Combet AM MP Targeting small and mediumsizes enterprizes for R&D Tax support Joint media release 17February 2013

12. Hon Greg Combet AM MP Boost to Australia's VentureCapital Market Will Drive Innovation Joint media release 17February 2013

13. http://afr.com/p/national/tax_concessions_undermine_asian_VCcGWCYpO9HDH8Z34HA1yH

http://afr.com/p/national/jobs_plan_helps_overlooked_contractors_ri5TP4H1GcvkFDLf5pMHEK

http://afr.com/p/national/gillard_to_defend_manufacturing_tq0nGVx9txl8VMopvE29tM

http://www.theaustralian.com.au/national-affairs/treasury/big-business-canes-pms-1bn-innovation-bill/story-fn59nsif-1226579895139

http://www.theaustralian.com.au/national-affairs/education/benefits-of-precincts-a-mystery/story-fn59nlz9-1226579842259

http://www.theaustralian.com.au/national-affairs/unions-cheer-local-jobs-plan/story-fn59niix-1226579840100

14.http://www.chiefscientist.qld.gov.au/research-and-development/reporting.aspx

15. http://www.business.vic.gov.au/industries/science-technology-and-innovation/programs

16. http://www.qld.gov.au/dsitia/about-us/business-areas/innovation-policy/

17. http://saplan.org.au/

18. http://www.commerce.wa.gov.au/ScienceInnovation/

19. http://www.development.tas.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0006/39777/Tasmanias_Innovation_Strategy_2010.pdf

20. http://www.dob.nt.gov.au/industry-development/research-innovation/Pages/about.aspx

21. http://www.nbnco.com.au/index.html?icid=pub:hme::men:hme