PROGRESS 2050: Toward a prosperous future for all Australians

16/06/2020

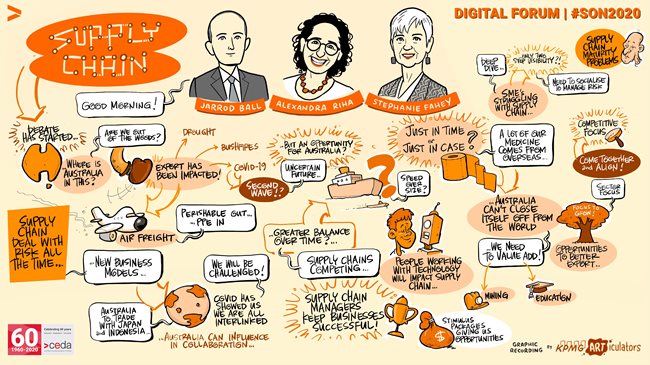

Dr Fahey was joined by Australasian Supply Chain Institute (ASCI) President, Alexandra Rhia, for a discussion of the effects that the COVID-19 crisis has had on global supply chains and the path forward for Australian trade and industry.

Dr Fahey described the difficult position that Australian exporters now find themselves in.

“There is no doubt that Australian exporters are doing it tough. We first had the impact of the drought, which was extended over many years, then we had the bushfires and now we have COVID-19,” she said.

However, she noted that the challenges have differed significantly between businesses.

“Those exports that were going by ship have not been immediately impacted – we can look at resources for example, which make up 70 per cent of Australia’s goods exports,” she said.

“But there is a group of goods exports that are dependent on air freight and most of our air freight was carried on passenger planes. So with the almost complete cancellation of passenger planes as we have progressed through these months, it has really impacted on the capability of our exporters, particularly exporters of perishable products, to get their products to the market.

“When we look at services exporters, our two major service exports are international tourism and international education, and they too are connected to passenger planes. As borders close, all of those industries have been very deeply impacted.”

Speaking about the risk of further outbreaks, Dr Fahey said that uncertainty has made decision making difficult.

“From the Australian point of view, we need to take this as an opportunity to think about how we can best navigate and remain agile and nimble. We don’t have control over the uncertainty, but we do have control over how we support our businesses and help direct our businesses into niche markets,” she said.

Alexandra Rhea reflected on the lessons that supply chain professionals can take from this experience.

“COVID-19 has made it even clearer that everything is interlinked. Changes in Brazil or China or Japan can have a huge impact on us here in Australia. The experience so far has shown the vulnerability of supply chains,” she said.

“The most curious thing about the COVID-19 crisis is our lack of visibility and we are facing this at all sides. On the supply side we don’t know how suppliers or sub suppliers are affected; we don’t know how customer demand is evolving and freight difficulties mean we don’t always know how to serve the customer best.”

Ms Rhea believes we have some cause for optimism moving forward.

“I am positive because I think we have seen most of it and we are now much better prepared. I believe that there will be surprises moving forward, but never again at the scale that we have just seen,” she said.

Dr Fahey discussed the ways that COVID-19 was challenging conventional wisdom in trade and supply chains.

“It has always been accepted that you should have lean inventory and extended supply chains, but we have seen how that played out when the pandemic started to hit the Australian economy. This led to conversations about whether we should have ‘just in time production’ or ‘just in case production,” she said.

“When we dig into the data you find that 90 per cent of Australia’s medicine is imported. When we are so reliant on medicine from overseas, we need to have a discussion about how we can be better prepared.

“So I can understand those who are saying that we should re-shore our manufacturing and build our own sovereignty, but as we also know that comes at a cost. It comes at a cost of increased redundancy within supply chains, making products more expensive. We also know that if we are producing all our own needs, we are not going to have the very best in the world by definition,” she said.

“We had a protective economy in the 1950s and we were very innovative in that period, but in the world of high tech can Australia really afford to close itself off to the global economy? I would argue not, if we want to maintain reasonable costs and maintain access to the best in the world.”

Dr Fahey said that the missing component in Australian trade is “value adding”

“We have good capability, we have strong industries in agriculture, mining, education and tourism, but there is the argument that rather than exporting expensive dirt we should be value adding,” she said.

“New businesses that centre around areas in which Australia has competitive advantage, such as education technology, will help to develop a more complex economy.”

Dr Fahey pointed to studies that showed Australia’s economic complexity is low by the standards of other developed countries and more in line with other resource rich countries, such as Kazakhstan or Senegal, that do not have a complex export profile.

“Australia has moved to a position where we are exporting goods and resources, but we are not value adding as much as we could. There are lots of opportunities to do that and I think we need to grow the complexity within manufacturing in particular,” she said.

“We shouldn’t stop exporting resources but we need an AND – resources AND. This will require focus – relentless focus – from government and business working in the areas of our competitive strength. In terms of sectors, it is my view that we should focus on sectors where we can be globally competitive and globally the best. It should be our ambition.

“We have a very strong research and development sector in Australia and we have an appetite now to align the research and development capability with business and government. As a team, we should feel that burning platform and acknowledge it and decide we are going to work together.”