Explore our Climate and Energy Hub

23/09/2024

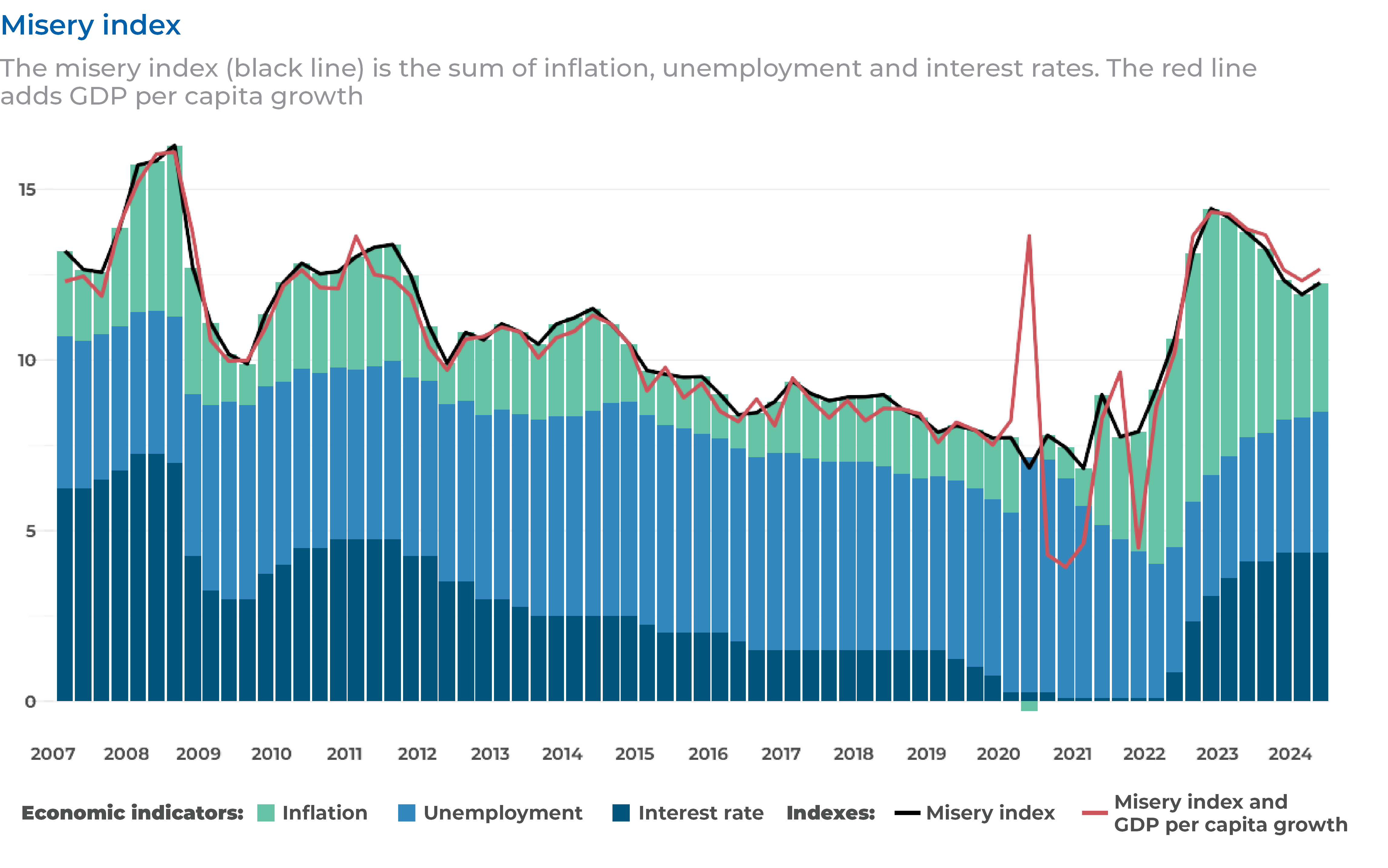

Australians are living through the most protracted period of economic misery since 2011.

CEDA’s analysis of the “misery index” shows Australians’ economic misery remains high in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic, and is starting to creep up again.

It also shows inflation accounted for around half of the misery felt by households between mid-2021 and mid-2023, reminding us we can’t be complacent about bringing down price pressures in the economy.

So how miserable are we?

Created by US economist Arthur Okun in the 1960s, the misery index combines inflation, unemployment and interest rates to offer a general view of the economic misery people are experiencing at a given point in time.

Gross domestic product (GDP) growth per person can also be included to provide a more nuanced analysis.

Misery rises when inflation, unemployment and interest rates are high, and economic growth is low.

A look at the index from 2007 to the end of June this year suggests Australians’ economic misery has fallen from the peak reached after the COVID-19 pandemic, but remains relatively high.

While in previous periods of economic misery high interest rates or unemployment played a greater role, this time inflation accounted for around half of the misery experienced by Australians between the June quarter of 2021 and the September quarter of 2023.

The chart also neatly highlights the difficult trade-off facing RBA Governor Michele Bullock.

Inflation remains stubbornly high, despite having moderated since its peaks. It continues to hurt households by forcing them to spend more of their income on the essentials of daily life.

Unfortunately, Bullock’s only tool to address this challenge – raising interest rates – also inflicts pain. As the index clearly shows, the combined effect of 13 rate rises since May 2022 and inflation is, well, miserable.

There has been a bump to the index in the most recent quarter, reflecting creeping unemployment as economic activity slows. Does this upward tick mean we could expect more misery ahead?

Most forecasts anticipate that the worst-behaved element of the index recently (inflation) will continue to ease over the coming year. As it does, the RBA will have increased scope to lower interest rates. With both measures falling, misery too should ease.

While the full impact of the stage 3 tax cuts and energy bill relief are hotly debated and yet to be fully realised, early data suggests they are predominantly being channelled towards savings, which will reduce upward pressure on inflation.

The resilient jobs market has also helped households maintain their incomes in the face of stubborn inflation and a faltering economy. The Reserve Bank and the Federal Government have both made it clear they want to maintain this strong employment picture.

The wild swings of the index between 2020 and 2023 when factoring in GDP growth per person (the red line) conjure images of a heart rate monitor in an emergency ward.

This is because when we include GDP, the index captures the cratering of growth at the start of the pandemic in 2020 as the economy suddenly ground to a halt – causing greater misery – and the rapid surge of activity afterwards as pandemic restrictions eased.

Australians made the most of their renewed freedom, spending more and bolstering the economy. These levels of robust growth supported a fall in the level of misery in late 2021.

Since then, interest rates and inflation have weighed on economic activity, with GDP growth per person negative for the past six quarters. A “per capita recession” like this naturally increases the level of misery.

Misery isn’t felt equally

It’s important to note the limitations of an index like this.

Inflation, interest rates and unemployment affect different people in different ways.

Those fortunate enough to own their homes outright or have large savings in the bank will benefit from higher interest rates.

But high inflation disproportionately hurts those on lower and fixed incomes with less financial wiggle room to cope with rising prices.

Nevertheless, the misery index does clearly illustrate what many of us feel to be true – things are tough right now.

The Federal Government and the RBA are trying to address these challenges, although their tools for doing so are not without risks.

Government policies that aim to help with the cost-of-living, such as energy-bill relief, can take some of the pressure off households. But they also risk putting too much money back into the economy, causing inflation to grow faster.

For the Reserve Bank, higher interest rates take money out of the economy to help fight inflation. But this engineered scarcity increases unemployment as well as the cost of servicing debt (which flows through to mortgages and rents).

The test remains for state and federal governments to ensure their policies work with, not against, the RBA, even if several also have elections on their minds.

Because if there’s one thing the misery index makes clear, it’s that policymakers need to be working towards the same goal – to bring down inflation while minimising the hardship caused by a softening economy.