Explore our Climate and Energy Hub

Economists have entered 2023 seesawing on their predictions for the global economy. The uncertainty that pervaded 2022 was driven by geopolitical tensions and the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic. These factors remain, but have been overtaken by rising inflation. Now, the primary driver of uncertainty is how far central banks still must go to tame price pressures, and the pace at which consumer and business activity cools in response to higher interest rates.

Amid this uncertain global outlook, Australian policymakers’ nerves will be tested throughout 2023. Barring any new external shocks, however, Australia will avoid recession. Higher interest rates and cost-of-living concerns will increasingly bite for consumers, and business will remain cautious until inflation begins to abate and there are more encouraging signs of growth.

Economic Outlook

Jarrod Ball

Chief Economist

There are still several factors that will bolster Australia’s prospects in 2023. Migration is rebounding strongly and China’s re-opening – and the improvement in Australia-China relations – will boost trade. This will add momentum to a recovery in services exports and maintain robust demand for Australia’s resources. In addition, consumers could well prove more resilient to inflation and challenging economic conditions than expected if the labour market holds up.

This backdrop reinforces the need for the Federal Government to bolster community confidence in 2023. It can do this by renovating economic institutions and settings that are vital drivers of stability and growth, beginning with its response to the reviews of the Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA) and the migration system, both due in early 2023. Further, it can continue to demonstrate that it is serious about fighting inflation in its second budget in May. The government must do this while continuing to navigate volatile energy markets and implementing new policies to accelerate decarbonisation.

There is little doubt that 2023 will be challenging for the Australian economy. It is the adjustment we had to have after the economic policies of the pandemic unwound and to bring down inflation. But Australia remains better placed than most advanced economies. If the RBA steers the right monetary policy course and governments introduce confidence-boosting policy reforms, Australia should be able to navigate the global volatility and emerge in a solid position.

CEDA's Economic and Policy Outlook for 2023

Read the full report now

Economic and Policy Outlook 2023

DOWNLOAD

The announcement of a new Housing Accord as part of last year’s Federal Budget shows housing policy is firmly back on the government agenda.

Many policy issues in this area in recent years have arisen due to a lack of commitment to implementing research-backed initiatives. The Government will need to be willing to listen and act on the council’s advice and avoid implementing politically popular, but ineffective, measures.

As concerns over housing affordability and availability continue to grow, governments, the building industry and the community all want the Housing Accord to be a success. So how can we build on the strong foundation laid out in the accord to ensure it succeeds?

The Government’s focus should be on providing clarity around its commitments and who is responsible for delivering them; boosting direct government involvement through investing in social housing; addressing capacity constraints in the industry; and prioritising planning and zoning reform.

Housing policy back on the agenda in 2023

.png)

Cassandra Winzar

Senior Economist, CEDA

Concerningly, the percentage of higher density residential building commencements has been falling since 2016. The accord clearly acknowledges the need for reform of planning and local government regulations. Critical to its success will be the state and territory government commitment to work with local governments to deliver planning and land-use reforms that make housing supply more responsive to demand.

CEDA's Economic and Policy Outlook for 2023

Read the full report now

On the face of it, a commitment to building one million homes in Australia over five years is unremarkable. On average over the last ten years, around 200,000 homes have been built in Australia each year.

The accord does not define what “well-located” means, whether the one million homes need to be affordable, nor whether they are in addition to normal building activity. There is also no commitment to developing regional markets (many of which are currently struggling with extraordinarily low vacancy rates), nor addressing sustainability issues in the building and running of new homes.

There is no indication the target is grounded in an assessment of housing supply needs based on expectations of future population growth. The Australian housing stock is already supply constrained, and simply continuing to build at the same rate, while the population increases, will not improve affordability.

Economic and Policy Outlook 2023

DOWNLOAD

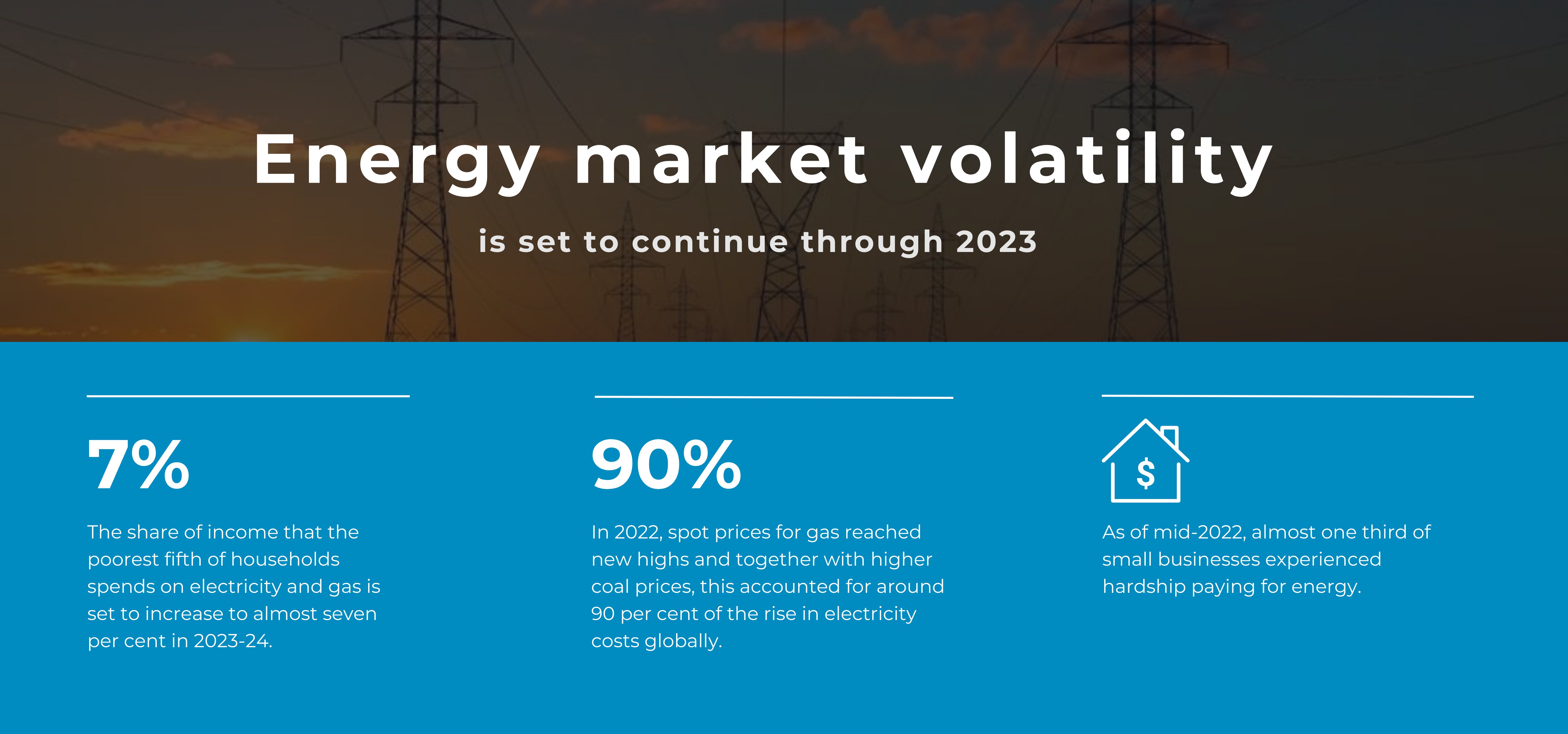

In the past year, electricity and gas have become increasingly unaffordable. Wholesale prices have soared and retail prices are set to reach record highs, resulting in a massive wealth transfer from energy consumers to producers. Not all energy consumers will have the same opportunities to manage their energy costs, with low-income households particularly vulnerable.

In this context, government should protect consumers from high prices, but support must be temporary and targeted, and avoid reducing investment in measures to lower energy usage.

Australian governments have imposed price caps on gas and coal to moderate increases in retail energy prices until the end of this year. The challenging geopolitical situation due to the war in Ukraine, coupled with a rapid transition to renewable energy, means the global outlook for energy prices remains highly uncertain. Governments must prepare now to ensure they have the best policy responses to current and future energy-market volatility.

Energy market volatility

.png)

Andrew Barker

Senior Economist, CEDA

Several factors combined to push up energy prices in 2022. The war in Ukraine added to already high international gas and coal prices in the wake of the pandemic, triggering a global energy crisis. Spot prices for gas reached new highs and together with higher coal prices, this accounted for around 90 per cent of the rise in electricity costs globally. High international fuel prices pushed up the cost of domestic fuel as Australian coal and gas became worth more in export than domestic markets. This, combined with coal plant outages, domestic supply shortfalls and hydro generating constraints, resulted in surging wholesale electricity prices in the National Electricity Market.

High wholesale energy prices are set to feed into record high retail prices over the coming year. These price increases will directly affect households as well as businesses, particularly small businesses that rely on retail energy. Already as of mid-2022, small businesses had seen electricity cost increases of up to 13.5 per cent, and almost one third of small businesses experienced hardship paying for energy

CEDA's Economic and Policy Outlook for 2023

Read the full report now

Low-income households spend a considerably greater share of their income on energy, so are most exposed to increases in energy prices. The share of income that the poorest fifth of households spends on electricity and gas is set to increase from around five per cent in 2021-22 to almost seven per cent in 2023-24.

Large households and those with higher-than-average energy consumption are more likely to experience energy-related financial hardship. This includes people living in regions with greater climate extremes and in housing with low energy efficiency, for example due to poor insulation.

On average, low-income households face an increase in essential housing and energy costs equal to around four per cent of their disposable income, with even greater increases for large households, renters in the private market and/or high energy users. Absorbing these increases in essential spending while keeping overall spending unchanged would require more than a 10 per cent reduction in discretionary spending on average for low-income households, consistent with surveys suggesting renters are being hit hardest by energy price rises.

The retail energy prices paid by consumers consist of wholesale costs of electricity and gas, as well as network expenses and retail customer service costs. Electricity bills also include environmental costs to fund renewable energy targets, feed-in tariffs for solar power and state government-operated energy efficiency schemes. Higher wholesale energy prices thus also send retail prices higher.

Wholesale electricity prices are linked to global prices of gas and coal, which are used to generate electricity. In the five regions of Australia’s National Electricity Market, wholesale prices are set at five-minute intervals based on power stations’ offers to supply electricity. The Australian Energy Market Operator (AEMO) dispatches the cheapest generator bids first, with prices set by the highest priced offer needed to cover demand. Gas and coal-fired generators usually set wholesale prices, so as their fuel costs rise, so too do their bids and thus also wholesale electricity prices.

Gas and coal are produced in Australia, but as they are traded in international markets, the domestic price is influenced by global prices. Higher global prices give local gas producers and coal miners an incentive to send their gas and coal to global markets, if their existing contracts and transport networks allow it. This leaves less supply in the domestic market, pushing up prices. There are overall economic efficiency benefits from this, as gas and coal go to higher value uses internationally, with exporters gaining windfall profits as a result. However, this can also bring substantial costs for energy users domestically.

To provide more transparency on movements in domestic gas prices, the ACCC calculates an LNG “netback price”. This represents the price gas producers could receive for exporting their gas, minus the cost of transport and converting the gas to LNG.

Economic and Policy Outlook 2023

DOWNLOAD

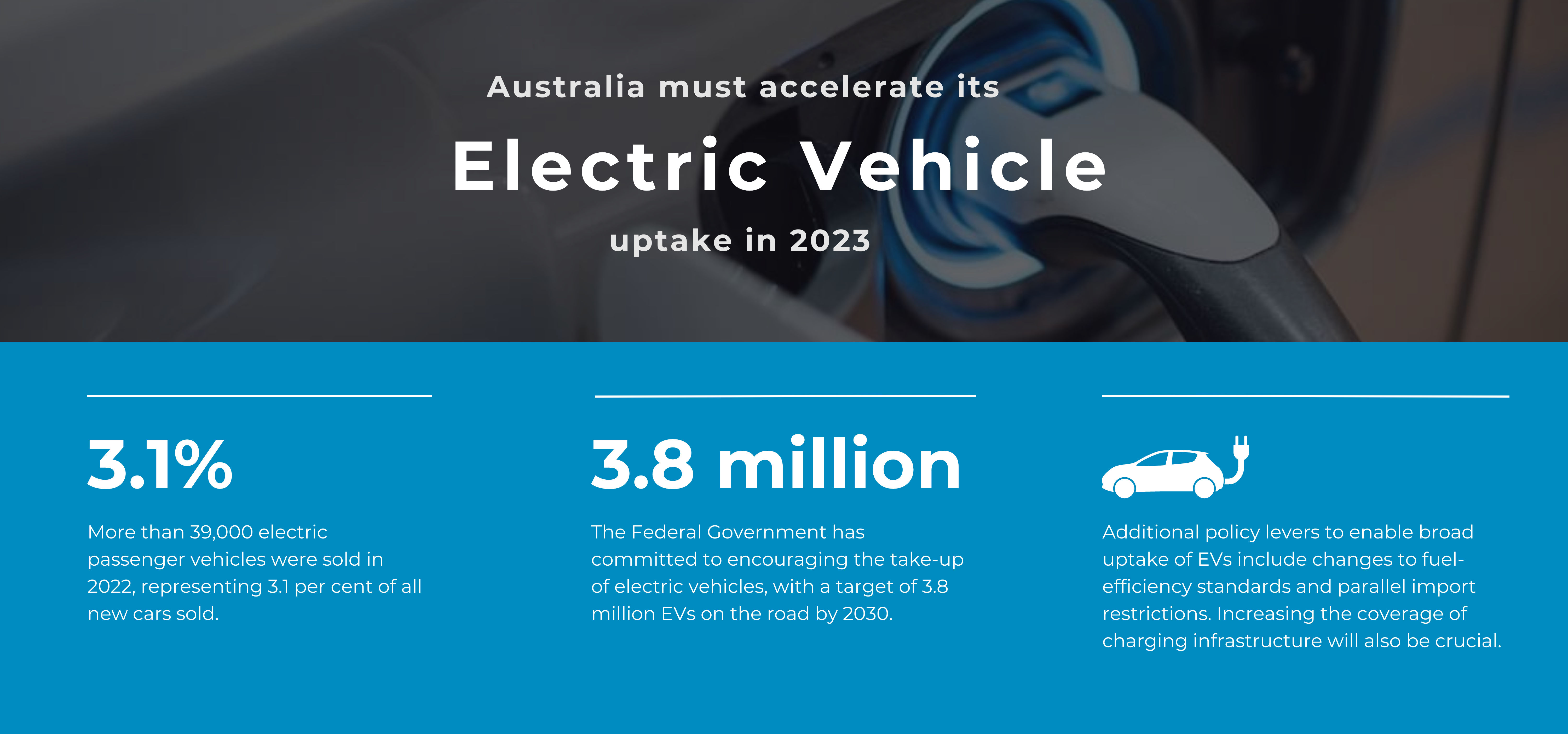

Transport is the second largest source of carbon emissions in Australia, representing 18 per cent of total emissions. Electric passenger vehicles (EVs) will play a critical role in decarbonising the sector, with current passenger vehicles accounting for 43 per cent of transport emissions. The electrification of commercial vehicles and public bus fleets will also have an important role to play.

Through its planned National Electric Vehicle Strategy, the Federal Government has committed to encouraging the take-up of electric vehicles. Yet its target for 3.8 million EVs on the road by 2030 implies adoption rates faster than we saw for household solar photovoltaic systems, an area in which Australia has been a world leader thanks primarily to strong policy incentives. Meeting this target will therefore require state and federal governments to introduce policies that promote take-up in the most efficient manner, a much larger variety of fit-for-purpose car models and more accessible charging infrastructure.

Consistency and coordination across government will be crucial to achieve this target. This includes a plan to fund road construction and maintenance as the shift from internal-combustion engine vehicles reduces revenue from fuel excise. Additional targeted subsidies will also be necessary to support take up among low socioeconomic households and drivers with long commutes.

Electric vehicles

Ian Hamilton

Senior Policy Advisor, CEDA

There are three key barriers to the uptake of EVs in Australia:

- Global supply-chain issues including shipping bottlenecks and microprocessor shortages have hampered production and availability. These are expected to ease in the next few years;

- There are fewer models available compared with similar markets, owing to our lack of national emissions standards. Consumers in the United Kingdom, which has emissions standards, can choose from 26 low-emissions vehicles under $60,000, compared with just eight in Australia; and Consumers are hesitant about battery range and charging-network coverage.

- Consumers are hesitant about battery range and charging-network coverage. Analysis for the Australian Renewable Energy Agency (ARENA) found with moderate growth in EVs, Australia would require more than 28,370 fast chargers to 2040, requiring an estimated $1.7 billion in total investment (excluding the cost of land).

CEDA's Economic and Policy Outlook for 2023

Read the full report now

To meet the proposed targets, Australia will need to adopt EVs faster than it installed solar photovoltaic (PV) panels (Figure 3). Since 2008, 3.3 million small-scale solar PV systems have been installed. The technology adoption rate for solar PV shows the potential experience for electric vehicles.

One key enabler of growth in EV sales will be ongoing demand for new cars as households replace their cars periodically. But governments must go further if we are to see the uptake of EVs outpace that of solar PV.