Explore our Climate and Energy Hub

30/03/2022

Let’s not be lulled into a false sense of security.

Our immediate growth is strong as we rebound from the pandemic, fuelled by the hangover from the sugar-hit of government stimulus and our skyrocketing terms of trade. But like most sugar highs, we will inevitably experience the challenge of withdrawal.

Our domestic economic growth will also face a hit, thanks to a reduction in global growth triggered by the inflationary pressures caused by the Russian invasion of Ukraine and inflationary pressures more generally; and a series of domestic factors such as rising interest rates and increased spending being directed to important but non-income producing activities such as defence, the NDIS and aged care.

Combined, this means that the national economic growth trajectory will slip.

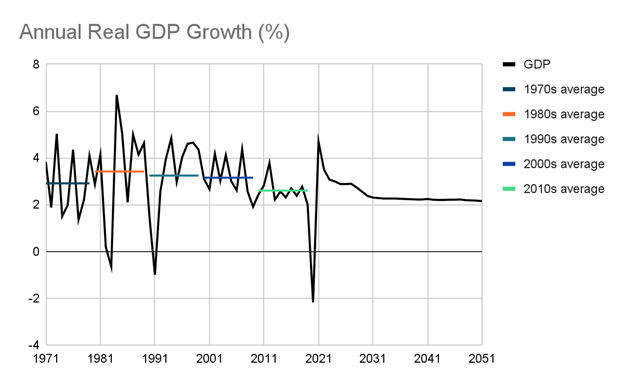

Indeed, the 2022-23 Budget projects real GDP growth in 2022-23 of 4.25 per cent, declining to 2.5 per cent in 2025-26. Taking an even longer-term perspective, as shown in the following chart, we see our real GDP growth declining over time to average growth rates lower than over each of the past five decades.

Source: PwC & S&P Global

This projected decline in economic growth reflects a series of long-term structural challenges, including declining productivity, an ageing population, and a projected fall in Australia’s terms of trade – that’s code for a fall in the iron ore and coal prices.

There are a series of implications associated with this long-term lower growth.

One of these is that fiscal repair will be more challenging for governments. With this lower level of growth, and in light of the revenue and spending commitments in the 2022-23 Budget, we project that the Commonwealth Budget will not return to balance until 2036-37.

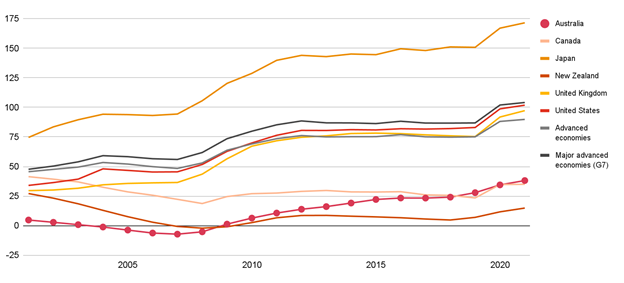

Related is the issue of government debt, the Commonwealth and state and territory governments – with the notable exception of Western Australia – subscribed to considerable new debt as a necessary measure to respond to the challenge of an effectively-closed economy at the height of the pandemic. Indeed, although still well below many comparable countries (see figure below), the Commonwealth has increased its net debt by 38 per cent since COVID-19.

Net debt as a percentage of GDP

Source: IMF

As a result, we now project that we will not reach zero net debt until 2060-2061.

While there has effectively been no extra expense associated with the cost of servicing this extra debt because of the reduction in interest rates, at some stage these debt servicing costs will increase and future generations will bear the brunt.

Should we be concerned and seek to pay this debt off as soon as possible?

The short answer is no.

History shows us what we need to prioritise.

World War II triggered a significant rise in public debt, peaking at about 120 per cent of GDP (in comparison to the projected peak of 44.9 per cent of GDP in 2025).

Australian Governments did not rush to pay the debt off, and in fact, never explicitly paid it off. Instead, during this time, Australia experienced a generational boom, with strong economic and wage growth, rapidly increasing material standards of living and falling inequality, all while running relatively modest government deficits.

The result was that the level of government debt to GDP fell sharply and was ‘largely eliminated by the beginning of the 1970s’ – 25 years after the end of the war. In effect, the combination of economic growth and inflation saw the economy outgrow the debt; the size of the debt became relatively less material as the economy grew.

Along with stabilising spending, growth should now be our priority after another (but different) cataclysmic shock.

PwC Australia’s post-Budget modelling shows the fiscal benefits available if we prioritise economic growth. If we can grow GDP half a percentage point faster per annum than we currently project (i.e., after the Budget’s forward estimates), then this would mean that we would:

- return to surplus six years faster

- reach zero net debt 15 years faster

It is easy to say ‘grow faster’, but how? And how does this year’s Budget help do just that?

Broadly, there are three levers Government can pull to grow the economy, commonly coined the ‘3Ps’:

- Participation – PwC’s recently released Women in Work Index shows that if Australia was able to increase female employment rates to Swedish levels, then Australian GDP could be expected to increase by nine per cent or US$125 billion. Last year’s major childcare reforms are explicitly aimed at this issue, and tweaks to the system are ongoing;

- Productivity – this is the real challenge as productivity is the only sustainable way to increase people’s real wages and living standards;

- Population – pre-COVID-19 we were relying on population growth – in the order of 250,000 people per year in net terms – to drive growth (i.e., the additional spending generated by simply having more people in Australia). This was lazy growth that prioritised aggregate growth rather than the living standards of each Australian (i.e., per capita growth). In policy terms, how we re-open the borders is an immediate challenge. Humanitarian migration, particularly in a time of conflict in many countries, is important, but we also need to focus on the re-emergence of migration to maximise productivity, focusing on young, highly skilled workers who bring the biggest economic dividends to Australia. Population growth needs to support productivity growth, not replace it.

In other words, we need to pull all three levers, acknowledging that sustained economic growth needs to be underpinned by sustained productivity growth.

So, what to do?

There are the old reform chestnuts that keep getting repeated: tax reform; industrial relations; regulatory reform (and particularly the reform of Commonwealth-state relations); and public service modernisation. These are mainstay recommendations because we are confident that reform in these areas address fundamental inefficiencies and will stimulate growth. But we also acknowledge that timing can be everything, particularly after a major global social and economic shock and particularly in an election year.

A number of measures in this Budget support future business-led growth and are particularly welcomed:

- the extension of employee share schemes to assist business to retain domestic talent and attract international talent;

- support for additional apprentices in priority industries;

- a reduction in the red tape associated with foreign investment to grow job opportunities;

- expansion of the patent box arrangements to spur innovation;

- changes to visa rules to assist in addressing workforce gaps.

The Budget is notable for its $17.9 billion of additional infrastructure investment, with a particular emphasis on connecting regions and markets to maximise growth opportunities. The challenge now is the realisation of these investments in the face of a real workforce challenge; the Budget’s new measures will not provide a panacea for this workforce crunch in the short term.

The Budget also commits to a range of industries and regions that we might not perceive as a strength now but are critical to our future prosperity: space; critical minerals, advanced manufacturing, and the development of Northern Australia and our relationship with India. Hopefully, this is the accelerant these industries and regions need to take off.

Going forward, we will need a laser-like focus on growth – growth that is both sustainable and equitable – that will inevitably require us to all embrace the shiny new reform things as well as the reform chestnuts that neither side of politics yet seems willing to tackle head-on. It’s an imperative becoming increasingly harder to ignore.