Explore our Climate and Energy Hub

Poor mental health is a cost to individuals, the community and the economy. The evidence shows that workplaces that invest in staff mental health have increased productivity, reduced absenteeism and more engaged staff.

This report focuses on the interventions and investments that businesses can make to improve productivity through wellbeing.

Our aim is to shift the conversation about mental health in the workplace to focus on the foundational elements of a mentally healthy workplace, including:

- Good job design

- A supportive organisational and leadership culture

- Strong management capability

CEDA will advocate on this issue with the business sector, government and other stakeholders, and actively promote the evidence on interventions that improve mental health outcomes for workers.

The outcomes we are seeking include:

- Mental health in the workplace to have the same standing as physical health and safety.

- A reduction in the rate of growth of mental health-related workers compensation claims .

- Improvement in productivity as shown through lower levels of sick leave and presenteeism.

- A broader evidence base and evaluation of mental health initiatives in the workplace.

- Improved awareness of the obligations workplaces have towards the mental health of their employees.

This is an area in which government, business and community all have an interest in pursuing better outcomes.

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

Poor mental health costs the Australian economy around $70 billion every year.

There is growing recognition that workplace health and safety is broader than physical safety – psychological health is just as important. However, this is much less straightforward for workplaces to address than physical safety and there is limited guidance available. Workplace responses to mental health are therefore often fragmented and lack evidence and evaluation.

It is estimated that 3.5 million Australians have mild to moderate mental health issues. Because of its size, this cohort likely has the largest economic and social impacts on the community. It is also an area where workplaces can have the most impact.

Australian businesses have been very successful in prioritising physical safety in the workplace in recent decades. Overall, serious workers compensation claims in Australia have fallen over the last two decades, while in stark contrast, claims for mental health conditions have increased. With even moderate growth assumptions, projected mental health-related claims are set to double by 2030. However, given the likely impacts of COVID-related disruptions, job instability and working-from-home these growth rates may escalate further.

The costs of workers compensation claims relating to mental health are also blowing out. Median compensation costs tripled in just under 20 years to 2018-19. With even moderate growth assumptions, in just over a decade they could triple again by 2030.

These outcomes are not inevitable. Employers can act to reduce the impact of work on employees’ mental health. This could lead to a drop in workers compensation claims, reducing costs for employers and improving employee outcomes. To do this, mental health must be prioritised to the same degree as physical health.

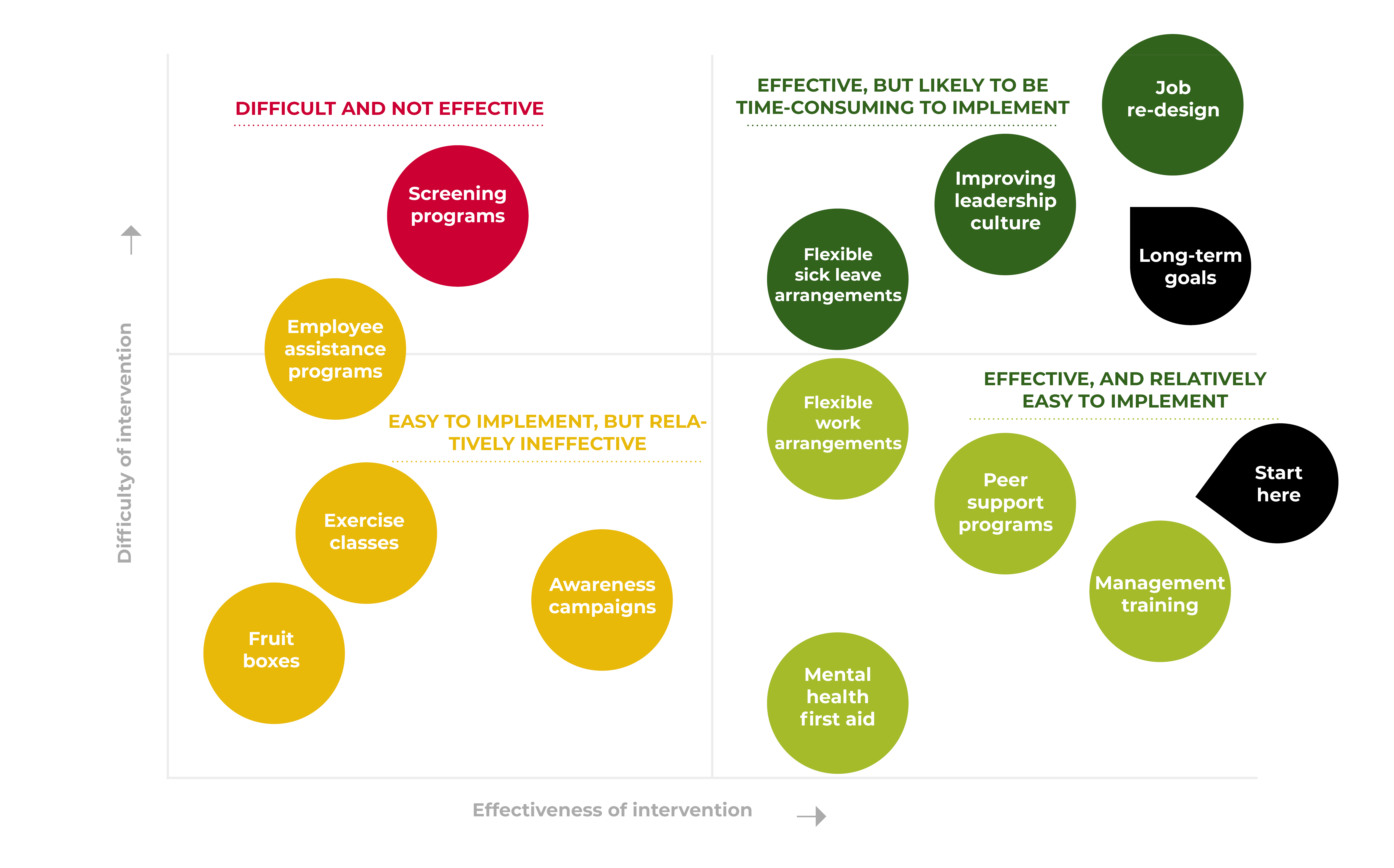

Investing in the mental health of employees is a sound business decision, leading to increased productivity and business outcomes. Many employers want to do more but need guidance on how to do so. Mental health in the workplace has often become synonymous with free yoga classes, fruit boxes and awareness morning teas. While these are simple to implement and high profile, the evidence shows they have little material impact on mental health outcomes.

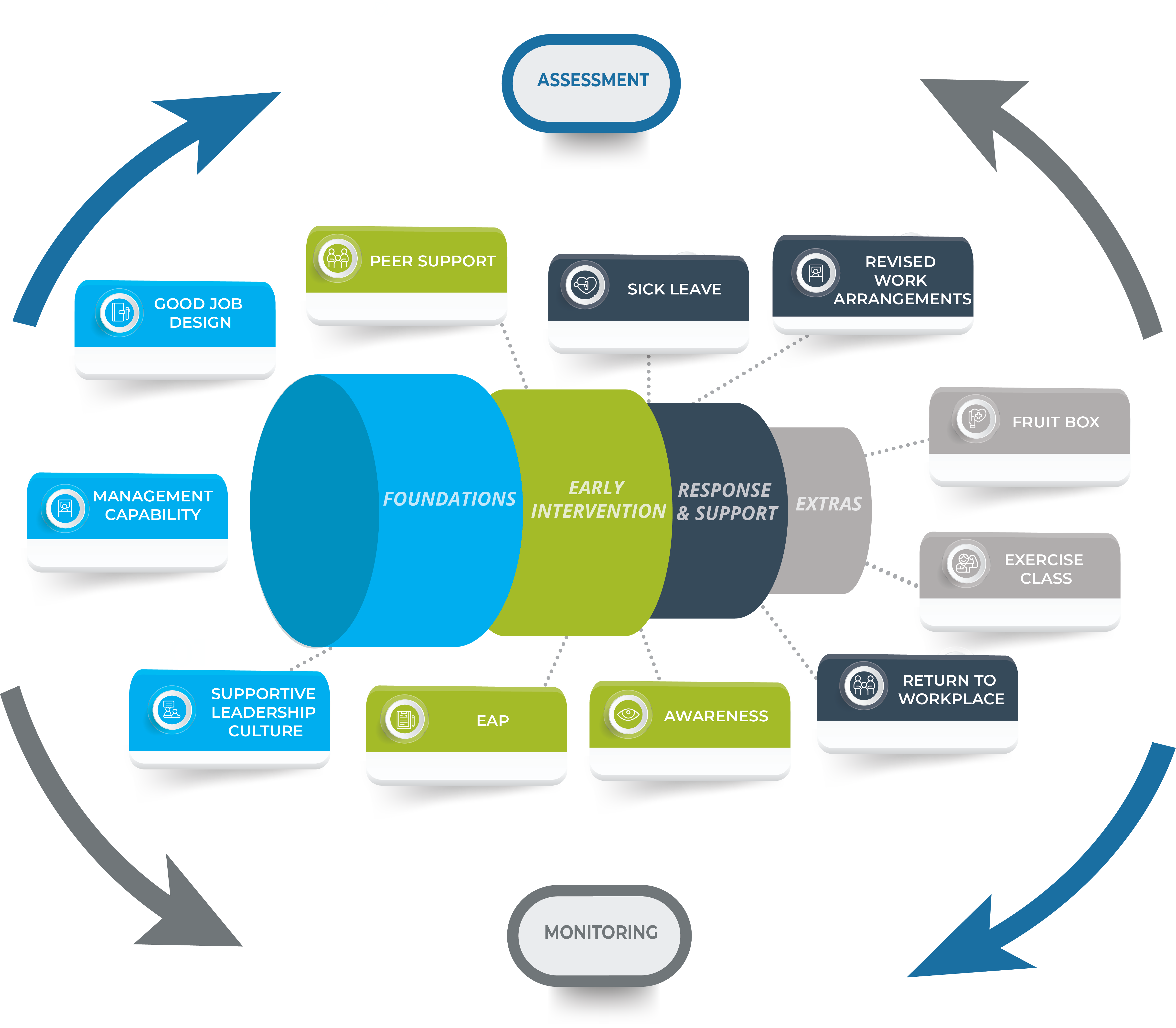

The available evidence suggests that the best returns are from businesses focusing on prevention and early intervention. Based on evidence and consultation with experts, we propose a framework for organisations that focuses on building strong foundations – through good job design, strong management capability and a supportive organisational culture. This will assist in preventing mental ill health before it becomes a problem. It requires appropriate support for all in the organisation to thrive, and individualised support for those that need it.

Where can businesses start to improve employee wellbeing;

- Prioritise mental health as much as physical health and safety in the workplace;

- Undertake an assessment of where their organisation is currently sitting with mental health, and implement ongoing monitoring; and

- Invest in the management capability of staff to identify and support workers with mental ill-health.

How does mental ill-health cost the economy?

The Productivity Commission’s Inquiry into Mental Health (2020) estimated that mental illness is costing the Australian economy around $70 billion per year, with a further $150 billion per year of associated costs of disability and premature death due to mental illness. Much of this is preventable.

Directly relating to the workplace, the Productivity Commission estimates costs of between $12.2 billion and $39.9 billion per year due to loss of productivity and participation. Mental illness and ill-health leads to lower rates of workplace participation, increased rates of absenteeism in the workplace and ‘presenteeism’ – where staff attend work but have low productivity. Firms also have further costs associated with staff turnover due to mental health issues. These costs are significant and are borne by workplaces. There are likely to be high returns from improving the mental health of the workforce. There are also positive impacts on overall employee engagement and relationships with teams and colleagues.

Outside of the workplace there are further benefits to individuals, communities, and the economy from improving mental health. Improving mental health issues can reduce pressure and costs on the health and hospital system, reduce government costs from unemployment and disability benefits, and improve social cohesion.

Mental Health and the Workplace

Cassandra Winzar

CEDA Senior Economist

What is mental ill-health in the workplace?

The Productivity Commission estimates 3.5 million Australians have mild to moderate mental health issues. The project focuses on this cohort of employees as it is a group where workplaces are most likely to have an impact as well its sheer size resulting in the largest cost impacts on the economy. Mental health issues or mental ill-health for the purposes of this report is broadly defined as employees having symptoms or conditions that show some level of psychological distress. This may be broader than employees that have a clinical diagnosis of a mental disorder or illness.

With a focus on prevention and early intervention, we are looking at promoting high levels of mental wellbeing before, or to prevent, employees developing a mental illness or disorder. This means providing some level of support to all employees, whether or not they have a diagnosed condition. In terms of the regulatory environment this is often described as reducing psychosocial hazards in the workplace.

Many risk-based or safety approaches to mental health only consider mental health issues that are caused by work or the working environment. This can be difficult to define and disentangle from mental health issues more broadly. Viewed through a lens of improving productivity, any mental health issues that are experienced at work or affect workers are worth employers paying attention to, whether or not work is a direct cause of the issue. Many factors that influence mental health outcomes will be unique to an individual – some of which can be influenced by the work environment and some of which cannot. An individual’s mental health will be impacted by events and influences from all aspects of their lives, and may impact their work. A supportive work environment can limit the impacts of other stressful events on work performance and productivity.

The argument for workplaces to intervene to improve mental health outcomes for their staff does not remove the need for individual responsibility. But it acknowledges that work is a substantial component of most people’s lives and that mentally healthy workplaces benefit not just individuals but also businesses themselves.

Mental health and workers compensation

The impacts of mental health in the workforce are broader than those that end up in workers compensation claims, which are serious in nature and directly attributable to work related events. However, it is useful to look at the trends in workers compensation claims as a proxy for broader workplace impacts on mental health and costs to employers. Workers compensation payouts are very costly for employers, and can provide incentive for employers to invest in preventative actions.

Overall, serious workers compensation claims in Australia have fallen over the last two decades, with a 13 per cent overall reduction of serious claims since 2000. The largest falls have been in physical injuries. This reflects an increased focus on employer obligations for physical safety and reducing risks in the workplace.

In stark contrast, claims for mental health conditions have increased by nearly 60 per cent over the same time period. This may not necessarily reflect increased prevalence of work-related mental health conditions, but potentially awareness from both employees and employers around mental health and increased the likelihood of employees applying for workers compensation (although the rate of rejection remains very high). Mental health conditions have the highest levels of compensation, with median compensation paid of $45,900 in 2018-19, compared to $14,500 for overall claims. Similarly mental stress claims have a median time off work of nearly 27 weeks, compared to just seven weeks for all serious claims.

Projecting future growth

Mental health related workers compensation claims have grown particularly strongly over the last five years, with an average annual growth rate of 10 per cent, although there has been considerable variability in the rate of growth. Comparing this to the rate of growth in other mental health related statistics allow us to create scenarios for projected future growth. Mental health related Medicare services have also grown strongly, at an average rate of around 6.5 per cent over the last decade, and five per cent over the past five years.

Using the moderate growth scenario, mental health related claims could double by 2030, and under the high growth scenario they could nearly triple. However, the trend rates do not include data that covers the whole COVID-19 period. Given the likely impacts of COVID-related disruptions, job instability and working-from-home it is possible growth rates may increase further.

The trends are even more concerning when looking at the costs of claims. Median compensation costs per claim for mental health conditions grew from $14,300 in 2000-01 to $45,900 in 2018-19. If recent trends continued, median costs per claim could triple in real terms by 2030. There is clearly an incentive for employers to invest in the mental health of their staff, and reduce the rate of claims related to mental health.

Why should employers invest in mental health?

Employers have legal and regulatory obligations towards their employee’s mental health. Under the Work Health and Safety Act 2011 businesses must manage the risk of psychosocial hazards in the workplace.But compliance alone cannot be the driving force behind investment in mentally healthy workplaces.

Investing in the mental health of employees is a sound business decision, that can increase productivity and improve business outcomes. It has been well documented that unemployment is linked with poor mental health – not just through lower financial capacity but also through the social contact, sense of identity and shared purpose that employment can bring. But not all employment is equal. Workers with poor working conditions, low levels of autonomy and/or high levels of job insecurity are much more likely to have mental health issues. How the employee’s workplace and job is organised also has substantial impacts.

The Productivity Commission estimated that the cost of absenteeism from work due to mental ill health was up to $10 billion per year, due to people taking an average of 10-12 days off. People with mental ill health are also estimated to experience reduced productivity on 14-18 days per year – an estimated cost of $7 billion per year.

The available evidence suggests the returns on investment in mental health investment are high – driven mainly by increased productivity resulting from reductions in presenteeism. The Productivity Commission’s Inquiry showed returns on investment of between $1.30 to $4 for each dollar invested for Australian workplace mental health interventions.

What is also clear from the research is the benefit of early intervention and preventative approaches. In a global study, Deloitte found stronger returns from proactive mental health support and organisational culture changes than from reactive approaches. The most effective programs are embedded in the organisation’s culture, long-term and offer a range of interventions.

There are also more general benefits to an employer from fostering a mentally healthy workplace. With changing attitudes towards the importance of mental health in the community and reduced stigma around disclosing mental health issues, employers should be looking for all options to promote their workplace – mental wellbeing being one of them.

There is a need for more evidence on what specific interventions can and will provide the best returns – this will assist government, industry and employers with how to target resources and promote investment in mental health.

Why do employers need to invest more in the mental health of their staff?

Previous research shows that Australian employers know that they have a responsibility to address the mental health concerns of their employees. While there is an increasing number of businesses interested in mental health, the overall numbers taking sustained action remain low. A NSW Government survey from 2017 shows only nine per cent of businesses had a sustained and integrated approach to mental health in the workplace.

The Productivity Commission noted in its inquiry that most businesses want to have a mentally health workplace, but don’t know what measures to take to achieve one. Some employers also remain unclear about what an employer’s duty of care is and how to meet this standard in practice.

Several studies have shown that businesses most commonly cite a lack of resources and commitment from management as reasons for not doing more. This is reinforced by SuperFriend’s 2019 survey that identified a lack of skills amongst managers and commitment from leadership to improve overall staff mental health as the primary factors holding back better mental health outcomes in the workplace.

Many employers have good intentions in this regard but need guidance on what to do. There is limited evidence or evaluation of programs and practices within workplaces, despite significant and growing spending by employers. While there is limited data on overall spending on mental health programs, companies providing corporate wellness have seen estimated revenue growth of 5.9 per cent per year over the past five years, driven by increased demand for mental health programs. Total revenue for corporate wellness providers was estimated at $288 million in 2022, which excludes spending on in-house programs.

Where should employers focus their efforts?

While there is a need for more evidence on specific interventions on workplace mental health initiatives, the available evidence does show what the key elements of a mentally healthy workplace are. Many of these do not require significant new investments as they are strongly linked to organisational and managerial effectiveness.

Workplaces need to have a range of different responses across the spectrum of mental health. Evidence suggests that the best returns come from businesses focusing on the prevention and early interventions space. We suggest a framework that builds strong foundations – through job design, management capability and organisational culture. This will assist in preventing mental ill health before it becomes a problem. But businesses also need to be prepared with how to respond to employees with more acute or complex mental health issues or illness. This means there is appropriate support for all in the organisation to thrive, and individualised support for those that need it.

Framework for investing in mental health

Monitoring and assessment

Before implementing any interventions, organisations would benefit from first undertaking an assessment of where their organisation is sitting with addressing mental health and wellbeing. This provides a baseline for organisations, allowing them to see what areas need the most improvement, and to measure the impact of any changes implemented.

Well established evidence backed tools such as the Thrive at Work assessment tool, the Safe Work NSW workplace pulse check or the People at Work tool, are good starting points and are easily available to assist businesses in assessing where they are at with mental health.

Organisations can take an approach of progressive initiatives and continuous improvement measuring mentally healthy workplaces, planning for improvement, evaluating success and collecting data.

Collecting, analysing and using data on the mental health of the workplace is a key component of monitoring and evaluation and the National Workplace Initiative suggests using a range of existing data, including:

Workers compensation claims, absences from work, turnover rates;

- Existing financial data, such as overtime or consulting costs;

- Staff engagement surveys (one-off or regular);

- Focus groups; and

- Interviews, including exit interviews.

To get the most out of any survey or qualitative data, the workplace needs to engage with staff in a genuine manner, so that staff understand why they are being asked for input and are clear on the expected outcomes from the process. It is important that any data is interpreted within an understanding of the environment the company is operating in.

Much of the research and evidence around mental health interventions in the workplace is relatively new, and there is a role for continued testing and trialling of interventions to further build the evidence base. Employers should not be discouraged from trying an intervention, provided they are collecting appropriate data on implementation and impacts to expand the available evidence.

Assessments cannot be a one-off. Monitoring needs to be ongoing and part of a business-as-usual approach. This will allow organisations to be responsive to its changing needs, changes in the external environment and prioritise investments and resources as required. As many of the programs and interventions in the mental health space are relatively new, it is important that organisations evaluate their impact and continue to make strategic decisions about what to invest in over time.

Background

WorkSafe Victoria’s “Integrated Approach to Wellness” is an example of a successful state level mental health improvement program. The program was developed in response to the elevated levels of depression, anxiety and stress experienced by white collar professionals in the infrastructure construction industry.

Why was the infrastructure construction industry targeted?

The need for a preventative approach to mental health was determined after 2018 research conducted by Swinburne University of Technology found that the levels of depression, stress and anxiety in the construction industry exceeded the Australian norm by 37 per cent. These results are unfortunate, but unsurprising given the infrastructure construction industry is characterised by long hours, high job demands, low job control, poor workplace relationships, poor organisational change management, and low recognition and reward.

Who was involved?

The project was developed by leadership and culture consultant Lysander and piloted at the Mordialloc Bypass freeway project with employees from construction companies McConnell Dowell and Decmil. It was funded by WorkSafe Victoria’s WorkWell Mental Health Improvement Fund.

How does it work?

As outlined in this paper, an important first step to addressing mental health in the workplace is conducting an assessment to determine where the organisation currently is. The Integrated Framework contains a Wellness Health Check which is designed to assist organisations to diagnose problems, develop a plan of action, focus efforts where they are needed the most and evaluate and reflect on progress.

Program alignment with the framework for investing in mental health

The program contains three themes which closely align with the elements in this paper that have been identified as foundation workplace interventions of strong mental health. These have been key to the program’s success.

TABLE 1

The Integrated Framework: theme alignment with framework for investing in mental health

| Theme | Description |

| Constructive and committed leadership (Management Capability) | Ensuring leaders demonstrate the behaviours and commitment to set and achieve goals that improve workplace mental health. |

| Culture and connection (Organisational and Leadership Culture) | Crafting and outlining the desired culture around bullying and harassment and reducing the stigma of mental health. |

| Communication and participation (Organisational and Leadership Culture) | Empowering employees to drive results through relevant communication that encourages participation. |

Senior leadership clearly plays a critical role in combatting mental ill-health. The program encourages leaders to be inspiring, have coaching conversations allowing them to tap into individual needs, and how to encourage participation to manage necessary change. The program also contained a list of tools, processes and documents aligned with the broader framework for investing in mental health (including a multitude of systems for monitoring performance in this area).

Evaluation and results

To clearly track interventions and outcomes, a baseline survey of the mental health of the employees was conducted in June 2020. This was followed up by conducting the same survey in January 2021. The follow up survey found improvements across work-life balance, burnout, stress and mood. Overall average levels of 'total mood disturbance' fell by 20% between the baseline and follow up surveys.

The survey research concluded with the following statement:

Improved wellness indicators at follow-up could be attributed to the direct impact of the application of the Lysander interventions upon individuals at the joint venture, given the notable improvement in mood, stress, burnout and work-life balance indicators of the 41 staff who completed both surveys.

The program was considered successful and is being rolled out across the industry. For example, McConnell Dowell reported that their client Major Road Projects Victoria has continued to support the program’s rollout across their road infrastructure projects.

Foundations – preventing and reducing mental distress on the job

JOB DESIGN

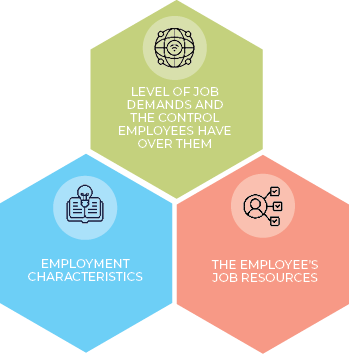

Initiatives to improve the mental health of workplaces should not be one-offs, but instead part of everyday work practices. There is strong evidence that job design promotes positive mental health outcomes in the workplace through enhanced employee wellbeing and productivity levels. Key aspects of job design include:

Job demands include the physical, emotional and cognitive demands of a job. Jobs with high demand tend to have higher levels of mental health risks, and increased levels of sick leave taken. This is particularly the case when combined with low control – how much decision-making authority the employee has. Jobs that are high demand and low control are generally classified as high-strain – and have the greatest risk of mental ill health. Flexible working is one aspect of job control, although certainly not the only one. The OECD notes that poor organisation of work and job design can play a role in the development of mental health problems. Research suggests that job demands and the degree of authority and autonomy a worker has over their work are key factors influencing worker stress levels, as well as the effort-reward imbalance – whether employees are rewarded (whether financially or otherwise) for their work. High level of work demands combined with low levels of autonomy causes negative mental health outcomes in the workplace.

The OECD has found that job strain across occupations has increased over time. This is particularly the case in lower skilled occupations – likely to be those with low levels of control over their jobs. It also finds that job strain significantly increases the likelihood of having a mental illness.

However, high levels of job control including access to support, feedback and learning opportunities, can reduce the impacts of high strain jobs. This allows employees to manage demand more effectively. A variety of tasks, and the opportunity to use skills is also important.

Jobs that are designed with a high degree of positive characteristics have high levels of autonomy, social support, feedback and lower levels of job demands. There is considerable literature showing links between good job design and higher levels of performance.

Employment characteristics have also been shown to have significant impacts on mental health including working hours, modes of employment and relationships with colleagues. Insecure employment and temporary contracts are associated with worse mental health outcomes for employees (see box 1).

Specific challenging or traumatic events may also confront employees of particular industries such as police officers, emergency responders, medical staff and the military. It is estimated that nine per cent of ambulance employees and 11 per cent of police employees have PTSD, compared to four per cent of the general population. Specific actions to address industry-based risks must be taken into account in these circumstances.

A survey of Australian businesses by AiG and Griffith University on what mental health interventions organisations were implementing, found that not one organisation identified job design as a tool to manage mental health in the workplace. The researchers note this is surprising given the strong evidence on the link between job design and employee mental health and wellbeing. This suggests a need for more awareness of the role of job design in workplace mental health.

The design on jobs is not fixed, and employers can re-design and re-configure roles to improve mental health outcomes. There is evidence that job redesign can benefit mental wellbeing, particularly when employees are engaged in the process of job redesign. Knight and Parker (2021) identify a number of factors crucial to the success of job redesign, including:

- Assessing and targeting areas needed for intervention

- Considering the context of the intervention

- Including employee participation in the design

- Assessing how the interventions are implemented

- Measuring the interventions against appropriate comparison groups.

Employment contract characteristics are a key element of job design. Precarious employment, where there is no, or limited, guaranteed hours of work or long-term employment contract has been shown to impact on mental health outcomes. The level of precarity can also be determined by poor pay.

When workers have limited guaranteed hours, or low rates of pay, they are more likely to hold multiple jobs. The Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) notes that over the past decade from 2009 to 2019, most industries have seen an increase in the rate of multiple job holding. Different aspects of poor job design can explain the increase. For example, the accommodation and food services industry is typically characterised by mass casual employment (insecure hours), while the construction industry has issues around unreasonably high job demands, poor workplace relationships and poor organisational change management. The greatest share of people holding multiple jobs by age in 2016 to 2017 were 25–34 year-olds. The median total employment income of multiple job holders was $40,500, below Australia’s overall median income, indicating either an environment of low pay or irregular/inadequate working hours.

The aged care sector is a clear example of the precarity of employment and job design more generally. While rates of casualisation in the sector are broadly similar to the workforce as a whole, more than 90 per cent of aged care workers were employed part-time. A large proportion of workers (30 per cent) would like their hours to increase, double the national industry average.

The Royal Commission into Aged Care noted the difficulty in retaining workers due to limited opportunities to progress to secure full-time work and subsequent full-time hours. This is compounded by the sector paying relatively low wages, ultimately reflecting the need for many workers having to hold multiple part-time jobs to increase their hours and income. This was shown in the 2017 Aged Care Workforce survey, whereby nine per cent of aged care workers reported holding multiple jobs. This is even higher than ABS figures for the March quarter 2021 showing the broader health care and social assistance industry recorded the highest rate of multiple job holding across the economy (158,700 multiple job holders or 7.6 per cent). Poor working conditions, as stated by the Royal Commission and highlighted in previous CEDA research, is another deterrent to worker and skill retention in the sector. The World Health Organization has noted that workers in low-paid, unrewarding or insecure jobs are likely to be disproportionately exposed to psychosocial risk at work, and those working in the care sector are particularly at risk, due to the type of work, and demographic background of workers.

Inadequate support (including lack of effective training), low wages and little opportunity to progress (increasing hours via full-time contracts) result in burnout and mental ill health – issues that have stretched the aged care workforce to crisis point and led to high rates of attrition in the sector. Precarious employment and multiple job holding make it harder for organisations to invest in the mental health of their staff and implement effective organisational cultural changes towards mentally healthy workplaces.

COVID-19 has undoubtedly changed the way we work and impacted key elements of job design. Government lockdowns and social distancing measures imposed throughout 2020 and 2021 caused the widespread uptake of working from home. In June 2021 the Australian Institute of Family Studies found that 67 per cent of employed people were sometimes or always working from home, compared to 42 per cent pre-COVID-19. This trend will continue with research from the University of Melbourne finding in 2022 that 64 per cent of employed people would like to continue working from home at least half of the time while one third would like to spend their entire work week at home.

Despite the many touted benefits, recent research from the Productivity Commission explored the potential downsides of working from home, including loneliness, negative mental health, and the blurring of boundaries between work and home. Furthermore, negative effects are diverse depending on gender, age, and household circumstances.

Despite this, survey results indicated that levels of loneliness and mental health did not differ between people who did and did not work from home. Furthermore, satisfaction with work life balance (a key aspect of job design) improved while working from home. Their overall conclusion was that there seems to be no evidence suggesting an increased risk to mental health for people who choose to work from home. Research on other countries comes to a similar conclusion. In their latest report, the World Health Organisation found small but positive effects of flexible working arrangements on mental health. They also referenced a study in Europe that found working from home was inversely related to absenteeism.

Job design is one of the three foundations for investing in strong workplace mental health. The increased level of autonomy that comes with the choice of working from home is an important aspect (albeit not the only aspect) to improving employee mental health.

How does this translate into productivity? Economist Nicholas Bloom’s research found results in favour of hybrid working arrangements. It estimated a five per cent increase in productivity due to re-optimisation of working arrangements and savings in commute time. Another Bloom study in July 2022 analysing the working arrangements of United States graduates found that attrition rates declined by 35 per cent and job satisfaction increased. This resulted in a small, but positive effect of 1.8 per cent increase in productivity. United States surveys show that the top three benefits of working from home are no commute time, flexible work schedule and less time getting ready for work.

As the significant uptake in working from home is relatively recent, much of the available research can only look at the immediate and short-term effects. As working from home increasingly becomes the norm, further research is needed to determine the long-term mental health and productivity impacts of such arrangements.

MANAGEMENT CAPABILITY

There is emerging evidence that management capability is one of the strongest contributors to positive mental health outcomes for employees. The OECD found that the manager’s attitude towards the employee is the most important factor that impacts on mental health, noting that a positive attitude from the manager reduces the probability of a moderate mental disorder by six per cent. A good manager can assist workers to cope with higher stress jobs. Improved training of managers and leaders can lead to higher levels of organisational resilience.

Managers often report feeling unsure what to do when staff are suffering from mental health issues. Research suggests that the confidence of managers in dealing with and discussing mental health with employees can reduce the prevalence of mental ill health in the workplace. Supportive relationships between managers, leaders and employees can reduce interpersonal conflict and support improved mental health outcomes. Furthermore, early and regular contact with managers during sick leave for mental health reasons has been associated with quicker returns to work and the largest predictor of whether managers did this was their confidence in addressing mental health issues. Increased training of managers can improve confidence through increased mental health knowledge, reduced stigma and increased awareness, leading to more supportive managerial behaviours.

Training for managers (all people in direct supervisory roles) on mental health has been shown to improve awareness and increase the confidence of managers in discussing mental health issues. Evidence suggests this also increases wellbeing of employees of managers that have undertaken such training. Manager training in mental health should help managers identify when workers might have mental health problems, respond to workers that need support, and understand how to adjust working conditions where required. It is not about managers diagnosing or treating mental health issues or becoming pseudo mental health care providers. A supportive leadership culture is required so that managers feel empowered and able to intervene and assist employees where required.

Industries with specific needs will need more tailored approaches. Some of these are already available such as HeadCoach for medical staff. Industry has an important role to develop industry specific manager mental health training.

The relationship between an employee and their line manager is one of the key factors in mental health outcomes for the employee. To get better mental health outcomes throughout an organisation, it is therefore worth investing in training for managers.

The intent of training is not to broaden a manager’s knowledge of mental health issues, but rather how to talk to their staff about mental health and be confident in having those conversations. This requires that managers are taught practical skills around having challenging conversations and are given an opportunity to practice those skills.

Research shows that managers with higher levels of confidence are up to 20 times more likely to make contact with an employee suspected of having mental health problems. In contrast, there is limited evidence of impactful outcomes from broader training in mental health literacy.

What training programs are already available?

There are manager training programs that have been evaluated and found to be effective. These are relatively low cost, scalable interventions built on a strong evidence base.

The Black Dog Institute has developed the HeadCoach online training program for managers which has been evaluated. This evaluation has demonstrated that it can improve managers’ confidence and lead to behaviour change that creates a more mentally healthy workplace.

Similarly, HeadCoach for Physicians was developed as a tailored approach for managers of junior doctors. The evaluation found that there was improved confidence and changed behaviour.

An evaluation of the face-to-face training program, RESPECT also found similar results. A group of managers from a fire and rescue service attended a four-hour training session on mental health. This led to a significant reduction in sickness related absence for the employees of those managers who had undertaken the training.

ORGANISATIONAL AND LEADERSHIP CULTURE

Important to the success of any interventions to improve mental health and wellbeing is the commitment and culture at the senior levels of leadership within an organisation. This includes a commitment to good working conditions and job design, policies and procedures for health and safety and a culture that supports and endorses mental health initiatives. Senior leader support has been shown to be the important link to implementing and facilitating interventions for workplace mental health. Workplaces are unlikely to see significant returns from any mental health initiatives without supportive leadership.

It is important to build a good ‘psychosocial safety climate within an organisation’, which evidence suggests improves mental health outcomes for employees. This includes balancing mental health and productivity outcomes. The Productivity Commission notes that making psychological health and safety as important as physical health and safety will generate net savings after implementation costs.

Leaders also have a role in modelling positive behaviours, including encouraging and participating in open discussions about mental health in the workplace. This is important to reduce stigma and build a supportive culture where people are comfortable speaking up and asking for support where required. Leaders who are actively involved in mental health promotion, model their commitment to stress management and prioritise positive mental health in the workplace can build a strong organisational culture that contributes to lower rates of mental ill health. This could start with leaders undertaking a self-assessment of their leadership style and impacts on mental health.

Few organisations have formal mental health and wellbeing strategies. An organisation wide mental health strategy, supported and championed by the board and senior leadership can be a way to show the organisation’s commitment to the mental health of employees and should be created in consultation with employees. There should also be clear roles and responsibilities at a senior leadership level around mental wellbeing. Business could consider where responsibility of mental health sits in the organisation. It often sits with a risk or health and safety role. There is an argument that it is more of a core human resources role – with a focus on thriving, not just managing risks.

Leadership style is also important, with evidence that ‘transformational leadership’ – creating a vision of the future with a focus on inspiring and motivating, can improve employees’ mental wellbeing. Positive leadership styles can improve trust and build a supportive environment for employees.

Early intervention

Early intervention, with a focus on awareness and wellbeing is important to ensuring positive mental health outcomes and shorter recoveries from periods of mental ill health. While there have been improvements in recent years, stigma around mental illness continues, which can make employees less likely to speak up or request assistance delaying appropriate support or treatment – lengthening recovery times.

Awareness and improving knowledge is part of reducing stigma around mental health. Training in mental health literacy (often as part of ‘mental health first aid’ training) has reasonable evidence in improving mental health knowledge, reducing stigma and improving confidence in helping others, or themselves. This training is not for employees to diagnose or treat mental health issues, but to encourage early support and intervention. For employees to feel confident in putting their training into practice, a supportive organisational culture and appropriate resources are important.

Some organisations have attempted to promote early intervention through proactive wellbeing checks, such as screening for depression or psychological vulnerability. The available evidence suggests these are ineffective in most circumstances. These programs can also come with considerable risk, such as increasing stigma for employees, issues around confidentiality and misinterpretation of results. These programs are not recommended, except in very specific circumstances, such as where workers are exposed to very high risk of trauma.

Employee participation, including providing team-based training in new knowledge and skills has been shown to decrease symptoms of mental ill health while increasing productivity.

Formal peer support programs have had some success, particularly in organisations with repeated exposure to traumatic events. Peer support leaders are provided with some training which allows them to support colleagues and identify those who require more help. For trauma related peer support, formal post incidence procedures may be followed. Peer support programs may reduce stigma and encourage staff to access help or further services. Guidelines are available on developing peer support programs.

Employee Assistance Programs (EAPs), which provide confidential counselling and support to employees, are very common in Australian workplaces. A survey by AiG and Griffith University found EAP was the most common mental health intervention among those surveyed. The evidence on these are mixed, partially due to a lack of evaluation and a lack of quality standards across providers. Many EAP providers have relatively inexperienced practitioners and may not be providing high quality interventions. The Productivity Commission inquiry noted that most organisations that engage an EAP do not evaluate the service provided by them, and many do not even get a report on usage. Those organisations purchasing EAP services must ensure that they are getting a high level of service, with appropriately qualified staff. EAP alone is not enough for strong mental health outcomes in the workplace.

Response and support

For employees that are suffering from mental ill health, access to appropriate services and support can assist them to continue their employment or transition back to work. These supports will be most effective if the basic foundations of positive mental health outcomes are in place, particularly supportive and knowledgeable managers who are willing and able to make appropriate changes to working conditions.

Some employees may be unable to work and require leave due to mental illness. There is evidence that in most situations being in work has improved mental health outcomes and that the longer an individual is on sick leave, returning becomes more difficult. There is emerging evidence that partial sick leave – where employees have flexibility to do a reduced role and more flexibility around work hours and duties can improve outcomes for employees and the organisation. It is also important that employees remain in contact with the workforce during any period of absence.

In some situations, where the mental ill health is directly attributable to work, workers’ compensation claims will be required, and employers should be supportive where appropriate. The rate of rejection of claims is very high (at up to 60 per cent, compared to around 10 per cent for physical workers compensation claims) as it is often very difficult to attribute the illness to the workplace. Delays in treatment while claims are being assessed can delay recovery.

While many mental health services will be accessible through the general health system, in some cases there may be a role for employers to assist with access, whether financially or logistically, to ensure quicker and easier access to treatment.

Return to work plans have been used extensively for physical injuries and are now commonly used for mental health issues as well. There is some evidence that these are helpful, particularly when there is an element of cognitive behavioural therapy involved, but they need to be individualised and part of a broader treatment plan. The Productivity Commission noted that high levels of employer support, early contact with the manager as soon as injury or incident has taken place and assistance with lodging any claims has a positive impact on outcomes when employees return to work.

Added extras

Many organisations provide their employees with ‘wellbeing’ activities and benefits. This may be subsidised or free exercise classes, healthy meals, fruit boxes, massages or end of trip facilities. Wellness benefits are often a relatively inexpensive, high-profile way for organisations to show an interest in the broader mental and physical wellbeing of their staff.

There is certainly evidence that exercise and healthy eating have positive impacts on mental health. However, there is limited evidence on how successful these behaviours are. These activities are likely to appeal to those that are already undertaking them outside the workplace. These activities are also not likely to be helpful if they are not provided in an environment with a supportive organisational culture around mental health and wellbeing.

These benefits may be welcomed by staff but are unlikely to have any significant impact on mental health outcomes, particularly if the foundations of good mental health are not in place in the workplace. This does not mean that these activities have no value or should not be provided. However, they should be viewed as part of the employee value proposition, rather than core mental health outcomes.

The regulatory environment

There is growing recognition that a workplace’s duty of care towards their employees extends to mental health. The regulatory environment around workplace safety has required the management of risks to psychological health as well as physical health for some time, but it is moving to support greater clarity, awareness and compliance with duties in relation to psychological health and safety. In the regulatory environment things creating a risk to mental health are described as psychosocial hazards, as distinct from physical hazards that workplace health and safety has more traditionally been concerned with.

Safe Work Australia develops national policy relating to workplace health and safety and prepares model work health and safety laws that are then implemented and enforced by the Commonwealth, states and territories. The Commonwealth and most states and territories have implemented the model work health and safety (WHS) laws, with the exception of Victoria. Safe Work Australia has recently amended the model WHS Regulations to clarify duties for psychosocial risks, in line with a priority recommendation from the Productivity Commission’s Inquiry. Jurisdictions are in the process of adopting the amended model regulations.

The new model regulations explicitly state that psychosocial hazards in the workplace must be eliminated or minimised so far as is reasonably practicable by following the risk management. These control measures are predominantly around workplace organisation and job design.

The model WHS Regulations define psychosocial hazard as: a hazard that may cause psychological harm and arises from, or relates to:

- the design or management of work;

- a work environment;

- plant at a workplace; or

- workplace interactions or behaviours.

Safe Work Australia has also published a model Code of Practice on managing psychosocial hazards at work. Some states have also released codes of practice directly dealing with mental health and psychosocial hazards. For example, SafeWork NSW has the Managing Psychosocial Hazards at Work Code of Practice released in 2021 and WA’s Psychosocial Hazards in the Workplace Code of Practice released in 2022. These provide further explanation and more guidance on how to comply with WHS legislation.

Western Australia in addition has a code of practice specifically for FIFO workers in the resources sector. The Mentally Healthy Workplaces for Fly-in Fly-out (FIFO) Workers in the Resources and Construction Sectors addresses particular issues around mental health in a challenging work environment. This approach could be adapted for other higher risk industries.

Companies should be aware of their obligations under WHS legislation and the need to address psychosocial hazards and protect mental health. These moves to explicitly recognise and provide guidance on psychosocial safety are part of the picture to improving mental health outcomes, but should be considered as a baseline. Many businesses report that there remains limited guidance on how to address psychosocial risks through control measures. Companies that want to promote thriving organisations with high productivity will need to go further than a purely risk management focused response.

The changes to model WHS regulations are new, and there is likely a need for promotion to workplaces and education to understand their obligations. WHS regulators also need to encourage and enforce compliance where possible. But organisations should not be waiting for regulators to tell them what to do. The business case for investing in mental health is strong and employers should be proactive.

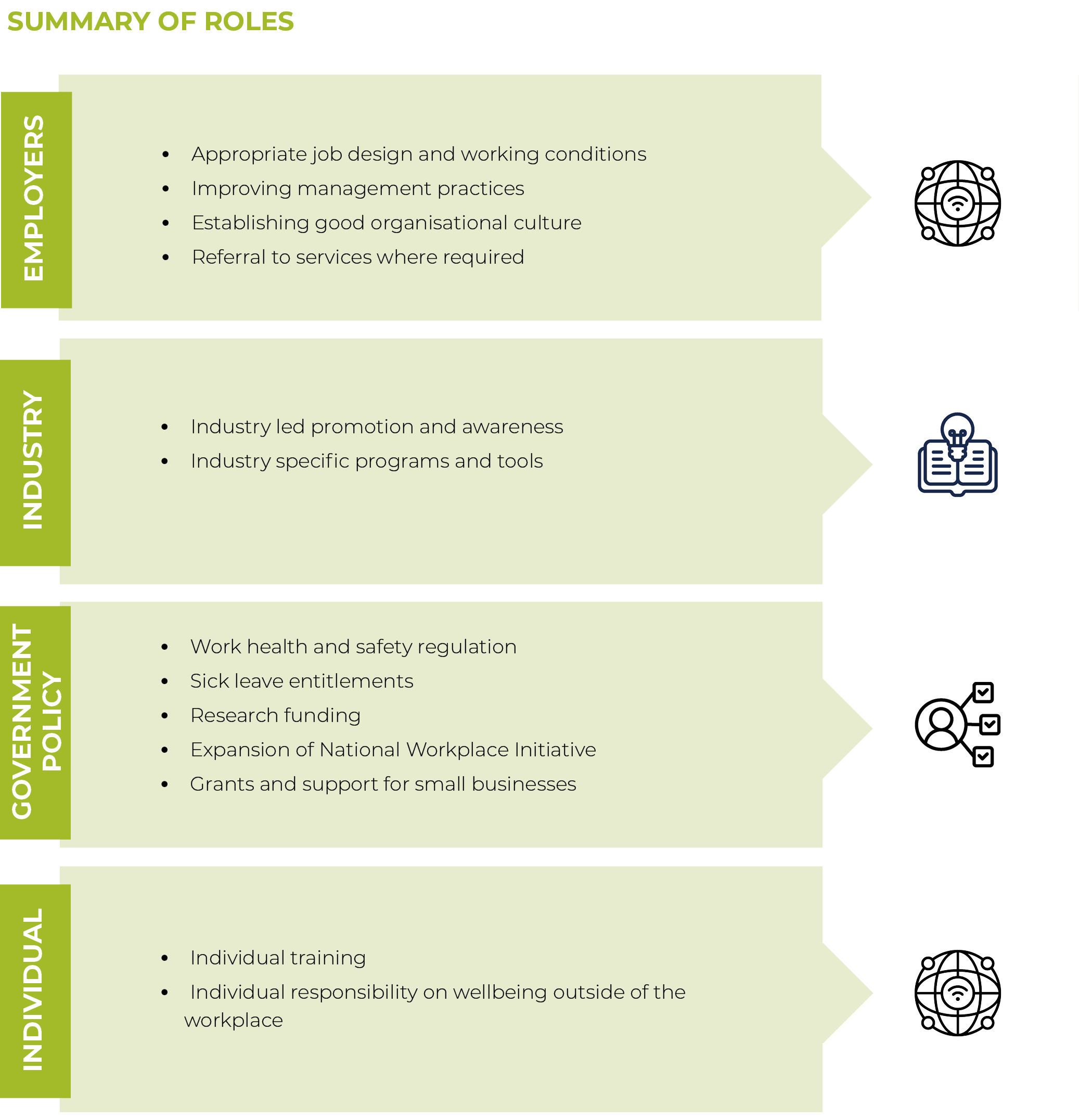

What is the role of different stakeholders?

This report has focused on the role of employers, who have the most control and ability to influence the foundations of a mentally healthy workplace. However, workplace mental health is complex and employers are only one part of the solution.

INDUSTRY GROUPS

There is a strong role for industry groups and peak bodies to play. This may include industry led promotion and awareness campaigns, particularly for industries with higher risk factors – such as difficult working conditions or exposure to trauma. There are positive examples of this across a few industries: MATES in construction or for FIFO workers. The National Workplace Initiative’s series on industry initiatives provides case studies and examples of how industry can establish these programs.

There is also a role for tailored industry training – such as the management mental health training or mental health literacy training. There is a role for industry groups to work with researchers to tailor training responses to specific industries to improve outcomes.

GOVERNMENT

Government has a role to play in the promotion of mentally healthy workplaces – both to improve productivity and business outcomes and also to lessen the pressure on the broader health system.

There are the regulatory issues described earlier in the paper, and governments should adopt the updated model WHS that explicitly includes psychosocial risks and provides guidance on application of the regulation. This may include industry specific codes of practice where appropriate.

There may also be a role for government in reviewing regulations for sick leave to more easily allow for partial returns to work and looking at the workers compensation system. The Productivity Commission has recommended that Workers compensation schemes should be amended to provide and fund clinical treatment and rehabilitation for all mental health related workers compensation claims irrespective of liability.

There is also a broader role for government to play in the funding and allocation of research. Workplace mental health remains an area that is under researched, with potential for more research and evaluation of where to best intervene for results. The National Mental Health Commission, through its National Workplace Initiative, is investing in providing an evidence base for workplace mental health and this role could be expanded beyond its current four years of funding.

At a state government level, there may also be benefit in grants, particularly for management training for smaller businesses, similar to the program Safe Work NSW provides for some businesses.

INDIVIDUAL

The role of the individual cannot be left out of this discussion. Individuals have a responsibility for managing their own health and contributing broadly to a mentally healthy workplace for themselves and their colleagues.

There may be some benefits to employers providing training that focuses on building personal resilience and problem solving, to enable individuals to build their own awareness and understanding of mental health issues or learn techniques for reducing stress and improving healthy lifestyles.

Employees are more likely to feel empowered to advocate for their own and colleagues’ health and wellbeing in a supportive organisational culture. Good job design will allow workers to better manage their own wellbeing and have opportunities for healthy lifestyle practices.

Summary of roles

Summary of recommendations for business: matrix

Businesses may feel unsure about where to start in addressing mental health in their workplace. While the suggested interventions will benefit the business as well as employees, many of them are time consuming and will not immediately show results. It is understandable that businesses often fall back on easy to implement initiatives such as healthy eating and exercise options. However, the research shows this will not achieve results.

Building a supportive leadership culture around mental health in the workplace, and redesigning jobs along established principles will provide good long-term improvements in mental health and productivity. These processes will take time and investment to be done well. In the meantime, there are steps that businesses can take that are easier to implement and backed by the evidence.

Conclusion

There is a strong link between employment and positive mental health outcomes and employers have a legal duty towards their employee’s mental health. But compliance alone should not be the driving force behind investment in mental healthy workplaces. Investing in improving mental health outcomes for staff is a sound business decision. Increasing mental health related workers compensation claims add to the argument for employers to understand their obligations and increase their interventions around mental health in the workplace.

With a focus on prevention and early intervention, we are looking at promoting high levels of mental wellbeing before employees develop mental illness. Businesses may feel unsure about where to start in addressing mental health in their workplace. It is understandable that businesses often fall back on easy to implement initiatives such as healthy eating and exercise options. However, this research shows that these initiatives are ineffective. Workplaces will need to have a range of different responses across the spectrum of mental health. The best returns will come from businesses focusing on the prevention and early interventions space. Our suggested framework focuses on building the strong foundations – through job design, management capability and organisational culture. However, businesses also need to prepare for how to respond to employees with acute or complex mental health issues or illness. This means there is appropriate support for all in the organisation to thrive, and individualised support for those that need it. These processes will take time and investment to be done well. In the meantime, there are steps that businesses can take that are relatively easier to implement such as investing in management training.

Australia has seen substantial improvements in physical safety risks in the workplace in recent decades. Making mental health as important as physical safety in the workplace will have significant dividends– for individuals, businesses and the economy.

_2.png)

Mental Health and the Workplace: How can employers improve productivity through wellbeing?

Download now